In the winter of 1925, a deadly outbreak of diphtheria in the remote port of Nome, Alaska, threatened the lives of the 10,000-plus living in the area. Children were especially at risk, and Nome’s isolation created a nightmare scenario. An antitoxin was located, but the nearest point which the serum could reach by rail was Nenana, located 674 miles from Nome. With a blizzard approaching, air travel was ruled out. Officials determined that the only way to deliver the serum in time was via sled dog teams.

A relay of 20 teams was assembled, including that of Leonhard Seppala, Alaska’s most venerated musher. Amazingly, in just five and a half days, the “Great Race of Mercy” was completed and the lifesaving serum was delivered to Nome. While the lead dog of the 53-mile final leg, Balto, would become famous for his role in the run, many argue that it was Seppala and his Siberian Husky lead dog, Togo, who were the true saviors of the day. All told, the 12-year-old Togo and Seppala traversed an astounding 264 miles, compared to an average of 31 miles each for the other teams.

For years, Balto, who also came from Seppala’s kennel, was celebrated, even earning a statue in New York’s Central Park. However, those in the know regarded Togo as the serum run’s unsung hero. Over time, with the help of historians, Togo began to garner the recognition he deserved. In 2001, Togo received his own statue in NYC’s Seward Park. In 2019, his story was retold in the riveting Disney+ movie Togo, starring Togo’s own descendant Diesel as the namesake Siberian. Most recently, Togo was featured in the AKC Museum of the Dog exhibition “Mush! A Tribute to Sled Dogs From Arctic Exploration to the Iditarod,” on view now through March 29th, 2020.

From Rambunctious Pup To Legendary Lead

The Norwegian-born Seppala first arrived in Alaska in 1900, when most sled dogs were burly Alaskan Malamutes or mixed breeds. Under the employ of the Pioneer Mining Company, Seppala began making a name for himself as one of the strongest mushers in Nome. Around that time, the first known Siberian Huskies in America were brought to Nome by Russian fur trader William Goosak. Those dogs, topping out around 50 pounds, would surprise by taking third in the annual All-Alaska Sweepstakes race in 1909.

That summer, English musher Fox Ramsay imported 60 of the finest specimens he found in Siberia to Nome. In 1910’s All-Alaska Sweepstakes, an all-Siberian team driven by musher “Iron Man” Johnson took first place in what remains a course record. Clearly, there was something to be said for these smaller, yet scrappy, Siberians as stellar sled dogs.

While whelping records from the era are scant, it’s generally accepted that Togo was born in 1913 to a dam named Dolly, who is regarded as a foundation bitch in the breed’s development. At the time, many of the Nome’s finest sled dogs were found in Seppala’s kennel. As a puppy, Togo suffered from health problems, and Seppala saw no use for the undersized, seemingly unfit dog. However, after being given away to a neighbor, Togo flung himself through a glass window and escaped back home. It seemed to Seppala that he was stuck with the incorrigible pup.

As Togo grew, he became captivated by the working sled dogs surrounding him. Still too young for a harness, he often got loose to run alongside teams training with Seppala, much to his owner’s anguish. His penchant for mischief led to a mauling when he ran up on a team of much larger Malamutes. Exasperated, Seppala decided to do what he did best with his dogs. He put a harness on the 8-month-old Togo and hooked him into the team. Togo ultimately ran 75 miles that day and worked his way up to lead on his first-ever time in a harness. Unwittingly, Seppala had found himself the perfect lead dog for which he had always yearned.

Togo & the 1925 Nome Serum Run

Over the years, Togo became known across Alaska for his tenacity, strength, endurance, and intelligence as Seppala’s prized lead dog. Togo led Seppala’s team in races and excursions long and short, and dog and man became inseparable. During this time, Seppala himself won the All-Alaska Sweepstakes in 1915, 1916, and 1917.

By the time the diphtheria outbreak struck in 1925, Togo was 12 years old and Seppala 47, both seemingly past their primes. However, with the fate of Nome in the balance, locals knew the aging yet experienced duo was their last, best hope. As deaths from the disease mounted, the decision to act was made. A multi-team dog sled relay was arranged to deliver 300,000 units of serum, already en route to Nenana by rail, the remaining 674 miles to Nome. On January 29th, Seppala and his 20 best Siberians set out from Nome with trusty Togo at the helm, to meet the westbound relay and retrieve the vital serum. Among those not selected by Seppala was Balto, whom the musher felt was yet unprepared to lead a team.

With temperatures hovering around -30 degrees, Seppala and his dogs made incredible time in their mad dash east, covering over 170 miles in just three days. All the while, the outbreak worsened back in Nome. Officials decided to add more teams to the relay, unbeknownst to Seppala. After cutting across the treacherously frozen Norton Sound to save time and distance, Seppala miraculously ran right into the team of Henry Ivanoff, one of the relay’s late additions, which was carrying the serum westward. The two teams nearly missed each other on the trail, but, thanks in part to the dogs, the connection was made. Naturally, it then fell to Seppala and Togo to bring the serum back towards Nome.

On the return trip across the Sound, the team became stranded on an ice floe. The quick-thinking Seppala tied a lead to Togo, his only hope, and tossed the dog across five feet of water. Togo attempted to pull the floe supporting the sled, but the line snapped. Amazingly, the once-in-a-lifetime lead dog had the wherewithal to snatch the line from the water, roll it around his shoulders like a harness, and eventually pull his team to safety.

Back on land after covering a near-impossible number of miles, Seppala and his team eventually made the serum handoff in Golovin, just 78 miles from Nome. Late additions to this final stretch of the relay included musher Gunnar Kaasen who, against Seppala’s instincts, had chosen Balto to lead his team. On February 3rd, 1925, Kaasen and Balto rode into Nome to a hero’s welcome. The serum had arrived, and the town had been saved.

The Legacy of Togo

While Kaasen and Balto were given much of the glory, it was Seppala and Togo who insiders knew had truly saved the day. In the years following the serum run, Seppala made trips to the Lower 48 states with his heroic sled dogs. Seppala traveled all the way to New England and took on a team of local Chinooks in a friendly sled dog race. With Togo in the lead in what would be his final race, the much-smaller Siberians triumphed.

Ultimately, Seppala and New England musher Elizabeth Ricker chose to open a kennel of Siberians in Poland Spring, Maine. It was there that Togo lived out the rest of his days in dignity and serenity. The indomitable dog was finally put to rest in 1929 at the age of 16. In 1932, Seppala returned to Alaska, whereupon the kennel closed and the dogs were delegated to friend Harry Wheeler. According to the Siberian Husky Club of America, all of the breed’s registered dogs of today can trace their ancestry to the dogs from the Seppala-Ricker kennel or Harry Wheeler’s kennel.

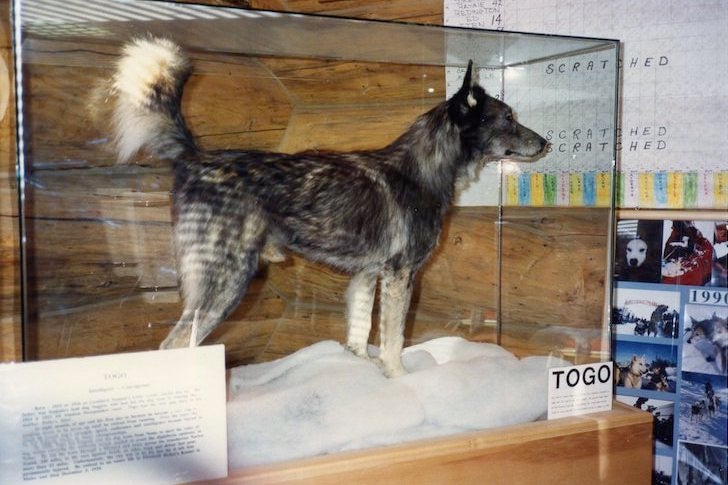

Over the years, more and more began to recognize Togo as the serum run’s true hero dog. Eventually, in 1983, his mounted body was given a place of honor at the Iditarod Race Headquarters in Wasilla, Alaska. Most famous among modern dog sled races, the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race is held each year in March, with parts of the route traversing the same 1925 serum run trails taken all those years ago.

Seppala himself passed away in 1967 at the age of 89. A fitting tribute, the Leonhard Seppala Humanitarian Award is given to the Iditarod musher each year judged to have taken the best care of their dogs. As for his thoughts on Togo and the “Great Race of Mercy”, which changed the course of his own life and dog sledding forevermore, Seppala summed it up thusly in his unpublished autobiography before his passing:

“Afterwards, I thought of the ice and the darkness and the terrible wind and the irony that men could build planes and ships. But when Nome needed life in little packages of serum, it took the dogs to bring it through.”

References & Further Reading On Togo:

Leonhard Seppala: The Siberian Dog and The Golden Age of Sleddog Racing 1908-1941 by Bob & Pam Thomas

The Cruelest Miles: The Heroic Story of Dogs and Men in a Race Against An Epidemic by Gay & Laney Salisbury

Togo’s Fireside Reflections by Elizabeth M. Ricker