Part 1 ended on a cliffhanger as the grey Toy Poodle Masterpiece owned by the flamboyant “Count” Alexis Pulaski went missing from his midtown Manhattan store Poodles, Inc. in spring of 1953. At the time of his vanishing, Masterpiece was surpassed in canine fame only by Lassie and Rin Tin Tin. He was, claimed his stricken owner, the most valuable dog in the world, a household name “at the height of his beauty and manhood.” And he was gone.

The Immediate Aftermath

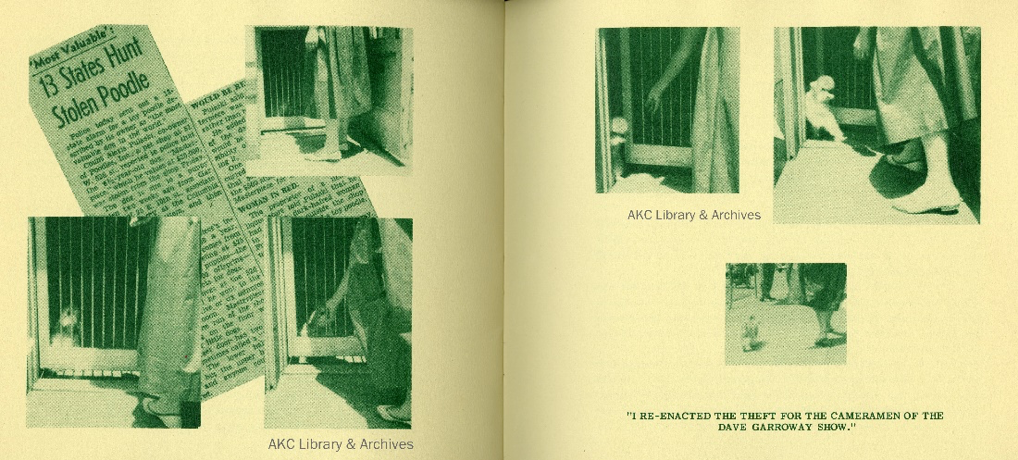

The police were quickly notified. Over the course of several weeks, a thirteen-state alarm was sounded. Newspapers ran headlines and Gotham Hosiery Company distributed 3,500 flyers seeking the return of its spokesdog. An ample reward was offered with the promise of no questions asked. Even a puppy sired by Masterpiece was offered in exchange for the return of the foundation Poodle. Just Johnny was selected from the remaining Pulaski stock as the dog most resembling his father. He was trotted out on television appearance with Pulaski, who recounted all of Masterpiece’s marked characteristics, pleading for his safe passage back to him.

Only one person came forward with credible information, claiming to have seen a small grey dog leaving Poodles, Inc. with a dark-haired woman in a red coat. A fashionable lady with a Poodle dutifully heeling by her side was at that time an increasingly common sight, however, this particular duo had resonated with the witness due to the absence of a leash. (“Masterpiece would obey anyone who gave commands in dog-show fashion,” Pulaski bitterly reflected later.)

The crime for which there were few clues was even re-enacted on “The Dave Garroway Show,” of which Masterpiece had been a recurring guest. Ponderously it showed the prized dog being removed from a cage, which is never mentioned in other remembrances of that infamous day. Whether it was simply faulty memory, a fib to make the Count appear less careless, or hints towards a more sinister coverup is unknown.

Alas, Part 2 cannot provide any closure, no substantive elucidation on the Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How of Masterpiece’s disappearance into thin air. It remains an unsolved mystery. The world will likely never learn the fate of its most valuable dog, will never know the intentions of its kidnapper, whether he was sold on the black market or lived out his days on a couch another borough, or another continent, over. Was it premeditated or impulsive? Someone he knew? Were they vindictive or out for money? Or simply for the superlative company of this most superlative companion?

One of the most piquant hypotheses is that perhaps Masterpiece just decided to leave all the pomp and circumstance behind, or at least take a brief respite. It was not the first time he had disappeared; once at nine months old, he fled into the woods. He was on his own for three days in the New Jersey countryside before returning, pert and perky, to the doorsteps of the kennel. A year later when Pulaski ran an errand, he had trotted out of Poodles, Inc. and fled the traffic into a Park Avenue linen shop which called the police and returned him home. As Pulaski himself admitted, “He undoubtedly realized that such a smart dog had little need of human supervision.” Whether by his own lucid choosing or not, Masterpiece was on to a new adventure from which he would never return.

Grief and Recovery

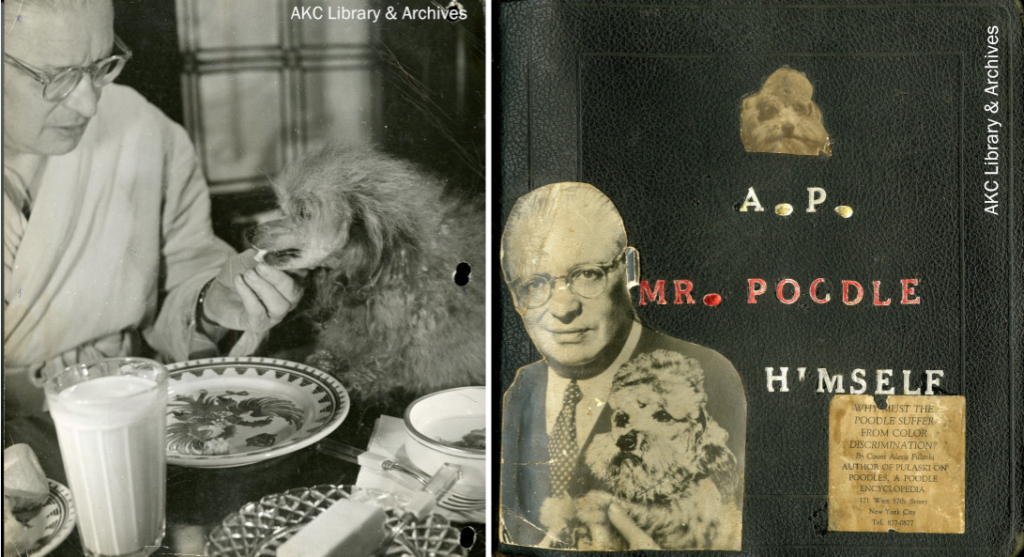

Pulaski issued annual monographs every year recounting Masterpiece’s doings, many written in the first-person by the celebrity dog himself. The first and last are held by the AKC Library & Archives. He claims later that they were issued in time for the holidays, costing several thousand dollars apiece. They are in actuality glorified booklets, bound by staples, copied from manuscripts fresh out of Pulaski’s own typewriter.

The introduction to the prematurely final installment reads, “Each year the booklets have been of a different color with the thought in mind that when Masterpiece was finally called to join the other dogs in the green pastures of their Paradise, the cover of the last booklet would be black – the traditional color or mourning. This I no longer believe I should do, for as long as his children, his grandchildren, and his great-grandchildren are living among us, Masterpiece in spirit will always be with us. I have therefore chosen gold – and green, the traditional color of hope. Hoping, of course, that Masterpiece will be returned to us that above all, hope that he is alive and happy wherever he may be.”

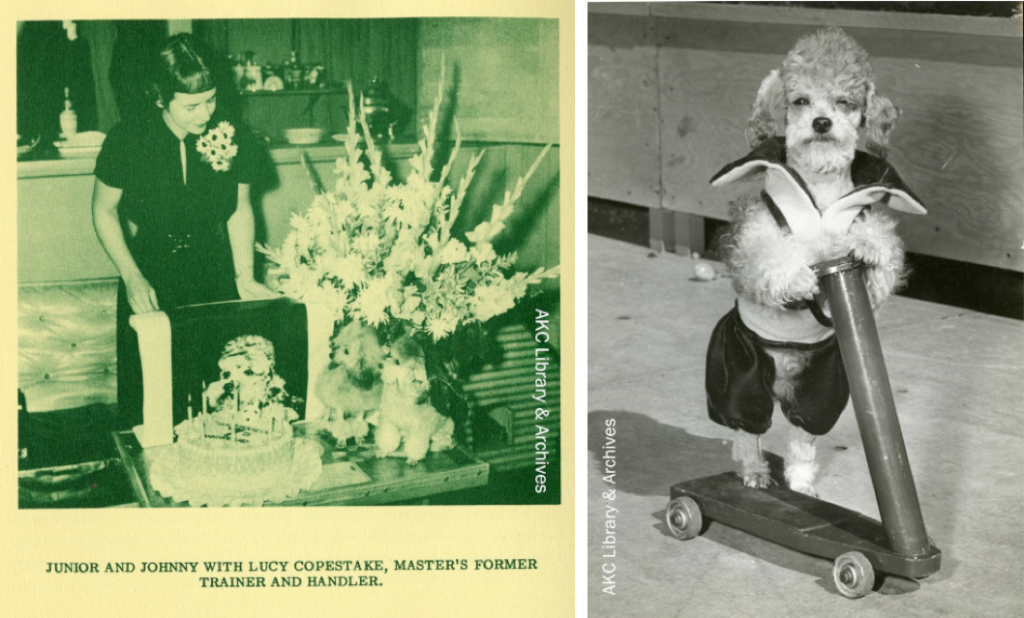

Just Johnny became the heir apparent to the Masterpiece publicity throne. He experienced a modicum of success as a $25/hr model and graced the society pages as “the most photographed dog in New York City,” but nothing near the heights of his paterfamilias. He was after all, “Just Johnny,” not a masterpiece.

A reporter from Louisville, Kentucky visited Pulaski a year after the kidnapping and found heightened security at Poodles, Inc., which had evolved into a shrine devoted to its departed mascot. Masterpiece’s green velvet canopy bed still sat in the corner. The walls were papered with photographs. They had recently held a birthday party for its guest of honor in absentia. Pulaski closed the store in 1956, but the cultural revolution it had inspired in how we choose, pamper, and adorn our dogs carried forth.

The Rise of Poodle-Mania

While it is difficult to imagine such an iconic breed basking in relative obscurity, the Poodle did not factor significantly into the early decades of American pure-bred dog ownership and exhibition. It began to gain traction amongst the dog fancy, with Charlotte Hayes Blake Hoyt claiming its first Best in Show win at Westminster in 1935. Hoyt wrote, “In the early 1900s fashionable society did not take up the Poodle and many of its members shared a general prejudice against it […] Until 1929, more were given away than were sold from the kennels that raised them […] a general feeling prevailed that the Poodle was somewhat of a sissy type of dog, and that it belonged to, at best, the Victorian Age, and at worst was a decadent, useless sort of animal.” Pioneers such as Hoyt (Blakeen Kennels) and Alene Stern Erlanger (Pillicoc Kennels) established strong breeding programs which proliferated, resulting in growth from only 50 Poodles registered with the AKC in 1930, to 835 in 1945, to 3,195 in 1950.

Poodles had also helped bring the concept of dog obedience to the United States, used in the earliest demonstrations performed for the American public by Helen Whitehouse Walker and Blanche Saunders beginning in 1937. Their intelligence and high trainability had also been on display as trick dogs in late 18th and early 19th-century circuses.

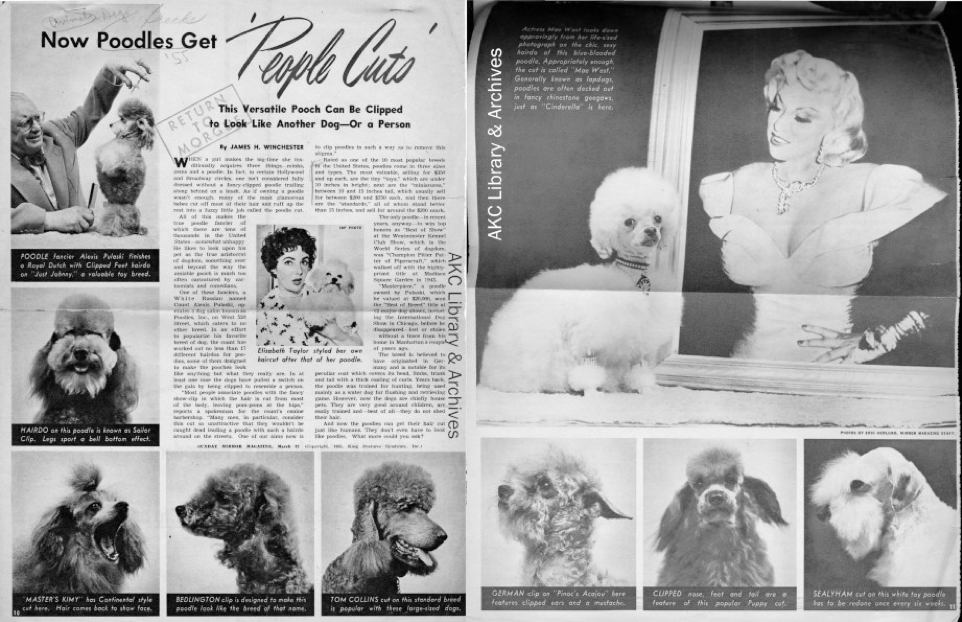

These virtues were often overlooked as the breed became a fashion plate by the 1950s. The era’s ultimate superstar Elizabeth Taylor was said to have modeled her shot gamine haircut after her pet Poodle, inspiring hordes of copycats. Saks Fifth Avenue and Abercrombie and Fitch reported that Poodle owners spent far more on their pets than other dog owners and that at Manhattan restaurants such as hot spot The Colony, Poodles outnumbered all of the other breeds put together. Wrote one paper at the time, “When a girl makes the big time, she traditionally acquires three things: minks, gems, and a poodle.”

Unlike most trends, this one was grounded in traceable logic and reason, as in addition to their appealing temperament and obedience, aesthetically Poodles were able to cater to myriad needs and aesthetic inclinations. Poodles offered more customization options than any other breed, as they came in three sizes (in order of market value: Toy, Miniature, Standard) and a variety of coat colors. They created the sense that one could abide by current tastes while tailoring to their own; conforming non-conformity if you will. Rinses even appeared on the market, enabling the dying of the coat pink, blue, or any color of the pet owner’s desire. For his part, Pulaski considered the rinses quite gauche, but offered at least seventeen different haircut styles including “The Mae West,” mirrored after the notoriously bawdy personality of stage and screen, and the “Sailor Clip” for a bell bottom effect in the legs.

A New Breed of Pet Owner

Dogs as accessories became en vogue, and so inevitably did accessories for said dogs. Mildred Pell, the designer whom Pulaski had commissioned for Masterpiece’s comprehensive wardrobe, later took her products to Hammacher Schlemmer and Bloomingdales. The retailers proved dubious at first until they all sold and Pell had to start hiring extra hands.

The New York Times ran a trend piece, blanketed in a tone half bemused half incredulous, on the indulgence of pet owners in 1960. It was estimated that Americans spent $150,000,000 annually on dog accessories, some practical (leashes, feeding bowls) but the increase was due in significant part to the proliferation of luxury items from four-poster canopied beds to black velvet opera capes to canine cologne (“Le parfum des chiens chic”), variations on products originally sold by Poodles, Inc.

New York was the epicenter of such overzealousness. An anonymous Manhattanite was quoted, “but it’s embarrassing in the city if your dog doesn’t have a nice velvet blazer when all the other dogs at its school do.” The Yellow NYC Pages of 1960 lists 41 “Dog and Cat Furnishings” establishments, 83 dog kennels, and 30 dog beauty parlors, which doesn’t even cover the dog departments of sporting goods and department stores or the establishments so exclusive as to remain unlisted. Upper East Side joint Poodles By Dana, whose proprietor Dana Miller was the sister of Afghan Hound legend Sunny Shay, offered a dog shampoo job for $88, a haircut for $70, and a manicure for $35 in 2019 dollars. She likely inherited the Poodles, Inc. crowd, and even its scandals, when in April 1958 the actress Monique van Vooren’s Poodle Fondini – with whom she shared matching mink coats and bikini bathing suits – was kidnapped by a stranger who claimed him under her name.

Back on the Scene

The New York Post reported in 1960 that one-third of the dogs in New York were purebred, growth from one-fifth only five years previous; 1 in 6 American dog-owning families included a purebred in its ranks, up from 1 in 100 in the 1920s. And atop them all was the Poodle, recently ascended to the most registered breed with the AKC, and by the largest margin yet recorded. It credited much of this development to one Alexis Pulaski. After four years of grieving, the “Count” returned to capitalize upon the new trends of his own making, “plunged back into the Poodle fancy with all his old enthusiasm,” and selling his dogs for as high as $3,000.

Later that year, the Post also reported that to their disbelief, Pulaski had followed through on his vow to devise an indoor bathroom for small dogs. It was claimed to fit neatly under the sink of the bathroom, automatically flushing water against the inside walls and the floor. It did not take off. He resorted to rabble-rousing in his bid for media attention, becoming a bit of a pariah among the dog fancy, arguing for show clips that didn’t “bear an uncomfortable resemblance to Rasputin,” and for the legitimacy of particolored Poodles barred by the breed standard. While some considered him a “menace,” most deemed him a relatively harmless kook. Wrote the AKC Gazette columnist in 1969, “as we all know, the old gentleman decided years ago that the army was out of step and went off on his own, breeding (and very competently) according to his own Standard of the Breed.” And in fact, Pulaski had begun designing his own colorful, ornately decorated pedigree charts on stiff parchment to accompany the purchase of his dogs, as if his own developed bloodlines were the only ones that mattered.

The remainder of his energy was devoted to his opus, “Pulaski on Poodles”, intended to be, perhaps incongruously, an encyclopedic breed history, an essential practicum on breeding and care, and a coffee table book filled with colorful anecdotes on famous and fashionable poodles. A scrapbook in the AKC archives contains the manuscript as well as the rejections from major publishers, who deemed it too similar to others under contract or too specialized. Smaller houses were unable to meet Pulaski’s overambitions for a fine quality gold-stamped tome that would be a conversation and display piece. As a last resort, he solicited $10 advanced purchases to finance an independent printing. A note backs up Pulaski’s claim that fellow Poodle enthusiast Winston Churchill requested a copy upon its publication, which ultimately never came to pass.

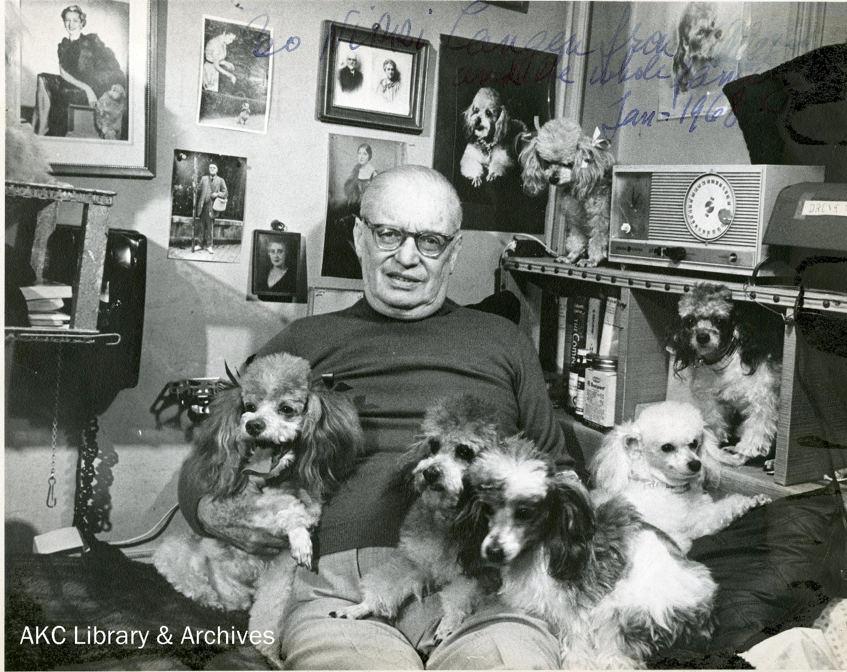

He appeared in a January 1968 New York Times feature on the popularity of the poodle, no longer traveling the world but still surrounded by his dogs. He also appeared on plaques from various kennel clubs, faded newspaper clippings and scrapbooks of his exploits, and pictures of the rich and famous holding Pulaski poodles. “Years of rebuff and ridicule have taken their toll, but Count Pulaski is undiscouraged and fights on with undiminished vigor,” the Times wrote. Only six months later, they were reporting his death at the age of 73.

The obituary largely reduced Pulaski’s legacy to Masterpiece, a sentiment he would have likely conceded. “I do not have talents or abilities to create an achievement of lasting usefulness for the world,” he admitted once, concluding he would make his contribution through dogs of such high degrees of companionableness they would create everlasting happiness. How tragic for him in that in recognition of the achievement of his ideal, he lost it.

In “Pulaski on Poodles” Pulaski originally titled his Masterpiece chapter, “The Story of an Amazing Dog.” However, the manuscript contains his handwritten edit to “The Saga of Masterpiece,” elevating his story to epic heights, its subject to the status of hero for the ages. He requests the reader allow him to “lean back in my easy chair, sip a pony of vodka, and reminisce…” about the little dog through which he achieved his “fondest dreams as a breeder.”

For all his hyperbole and ballyhoo, the bereaved “Count” emerges terribly relatable to anyone who has suffered the crushing loss of their pet, sustaining themselves on the memories. He knows the dog is surely dead, and that his celebration of him could be misconstrued as boasting, but he says he is only praising his “little friend.” When all is said and done, “Masterpieces are rare,” Pulaski concludes, “they should be cherished.”

Special thanks to the Poodle Club of America for donating its collection, including the Alexis Pulaski scrapbooks, to the AKC, enabling the rediscovery of this unique, otherwise forgotten, tale.

For more deep dives into dog history, check out profiles of legendary Afghan hound breeder Sunny Shay and Whippet pioneers the Shearer sisters, featuring content from the AKC Library & Archives collections.