The letter arrived in Molesey, outside of London, in June 1942, during the bleakest days of the war. Food and clothing were rationed, and citizens wore metal identification bands, in case they couldn’t get to their air-raid shelter before deadly Nazi bombs started dropping.

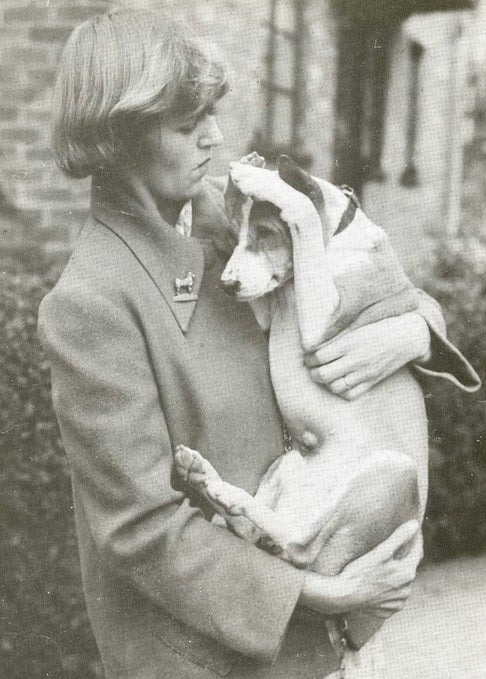

The mysterious letter from America also appeared to have been strafed, albeit by a government censor whose black slashes were visible throughout. Still, Veronica Tudor-Williams easily made out its contents.

“I spent last winter in the Southern part of the United States where I was born, where the Mississippi is more than a mile wide,” wrote James Street of New York City, whom Tudor-Williams had never met. “One day I stepped into a bar run by a friend and he showed me a picture in a magazine of a charming young lady with some dogs.”

The young lady in the photo was, and the dogs were her Basenjis – erect-eared, curly-tailed dogs from the rainforests of the Congo in central Africa. “I had never heard of the breed before,” Street admitted, describing himself as a “Bird Dog, Coonhound, and Foxhound man.”

But Street was also a writer, and he was intrigued by Tudor-Williams’ clutch of elegant African canines. Inspired, he wrote a series of stories about a Basenji lost in the swamps of Mississippi that were so popular they were to be published as a novel, titled “Good-bye, My Lady.”

“Good luck,” Street wrote from across the ocean, “and thanks for having your picture in an American magazine.”

Basenji in the Spotlight

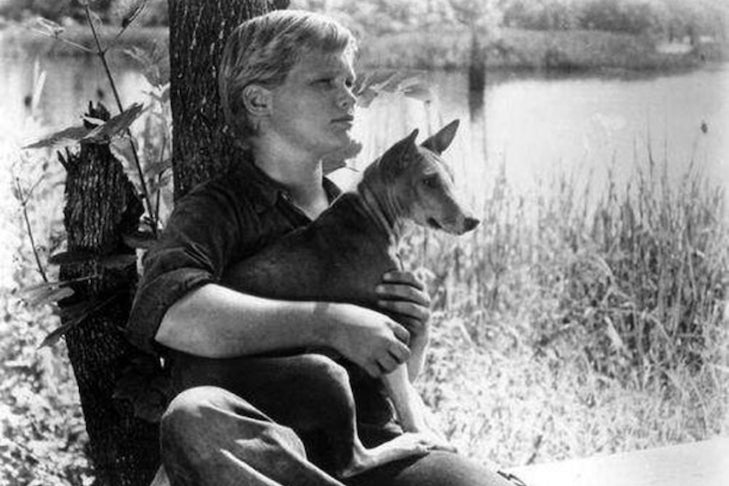

The story, of course, did not end there. “Good-bye, My Lady” – about a teenager raised by his toothless uncle who finds a mysterious yodeling dog wandering outside their cabin – became a best-seller. Hollywood perked up its own ears, and in 1956 planned to release a movie of the same name. It cast 13-year-old Brandon deWilde of “Shane” fame as the youngster who acquires the dog, only to find she has a rightful owner, and character actor Walter Brennan, who stands to get a new pair of choppers and a shotgun with the reward money.

The role of the Basenji, however, was still open. So Tudor-Williams received another communication from across the pond – this time, a 2 a.m. phone call from Hollywood. Tudor-Williams had just the Basenji for the title role – a precocious and photogenic 6-month-old female she named My Lady of the Congo.

In truth, the Basenji had already made its cinematic debut, however briefly, in 1951’s “The African Queen” with Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn, appearing on the lap of a native in a church scene at the start of the film. But compared to that eyeblink of a cameo, in “Good-bye, My Lady” the Basenji received top billing, and interest in the breed was piqued.

While this quick-witted, cat-like creature was new to most American theatergoers, the breed had left the central Congo more than a century before: In 1843, Queen Victoria was gifted with an “African dog” with hooded ears and fine bone from a captain returning from an expedition to Niger. In the 1920s, Lady Helen Nutting acquired a half-dozen Basenjis in South Sudan, only to have them all die after receiving the new distemper vaccine – which, unlike modern vaccines, could become virulent. Still, more British breeders struggled with vaccination losses, until the breed was finally established in the U.K. by the late 1930s.

The Land of the Barkless Dogs

For her part, Tudor-Williams returned to “the land of the barkless dogs” in an effort to get the native peoples to part with their treasured hunting dogs. Silently hunting birds and other small animals in the thick jungle vegetation, these intelligent, speedy dogs often wore wooden bells with monkey bones as clappers. They flushed game into the waiting nets of hunters, led the way to nests containing eggs, and exterminated rodents and other vermin in the villages.

“Owners apparently considered their Basenjis as precious as their children. Their dogs followed them quietly to heel and, if we stopped to observe, were picked up protectively in their arms,” wrote Tudor-Williams, who often drove 100 miles a day over dirt roads in search of the dogs. “I had been told that natives seldom parted with adult dogs — a statement I could hardly credit, but it proved true. Occasionally we saw a young adult that we wished to buy. Through our interpreter, we would offer jewelry, cigarettes, and finally large sums of money” – up to triple the price of a bride’s dowry – “but to no effect, the native owner walking away, a disdainful expression on his or her face.”

Undaunted, Tudor-Williams changed tactics, deciding to purchase puppies instead. But she soon found that word preceded their arrival, with the empty-handed villagers explaining the puppies had already been sold. In truth, they had been hidden because of rumors that the European visitors were looking to shoot them, a misunderstanding that Tudor-Williams guessed “stemmed from memories of the days when white men shot dogs because of rabies outbreaks.”

More Unique Than Most

The remote natural range of the Basenji has made it possible for modern breeders to return to Africa themselves for new imports. In 1990, the Basenji Club of America petitioned the AKC to open the studbook, and numerous successful Basenji safaris have ensued. Each import has been evaluated, and many have been approved and incorporated into the gene pool.

Every purebred-dog fancier considers his or her chosen breed to be unique, but the Basenji is arguably more unique than most, from its yodel-like vocalizations, which are due to the unusual flattened shape of its larynx, to its lack of a distinctive doggie odor. Unlike most modern breeds, Basenji females only come into heat once a year, similar to wild canids.

DNA studies have found that the Basenji does not cluster with any of other breeds, but rather holds a genetically distinct position of its own that predates not just the evolution of purebred dogdom, but likely agriculture itself: Research in 2021 found that, like wolves and dingoes, the Basenji has lower numbers of the AMY2B gene that produces amylase, an enzyme that helps digest starch. This is a hunter-gatherer’s dog, through and through.

If there was one criticism of “Good-bye, My Lady,” it was of the ending. In this coming-of-age story, My Lady’s young owner eventually returns her to her rightful owner. But real life, at least, turned out to be much more satisfying: The contract with Tudor-Williams stipulated that My Lady would belong to young Brandon deWilde once filming was complete.

So that’s a real-life happy ending for a boy and his dog – which, Basenji lovers would be quick to add, is not just any dog.