It was strange, eerie even, like one of those science-fiction movies where a person wanders into a town invaded by space aliens. No matter where you looked, there they were: little brown dogs.

They were romping on lawns, trotting into grocery stores, sailing by on shrimp boats, and peering out the windows of cars and pickup trucks. In the field, they could be seen pointing, flushing, retrieving, and any number of tasks that would usually require three or four different sporting breeds.

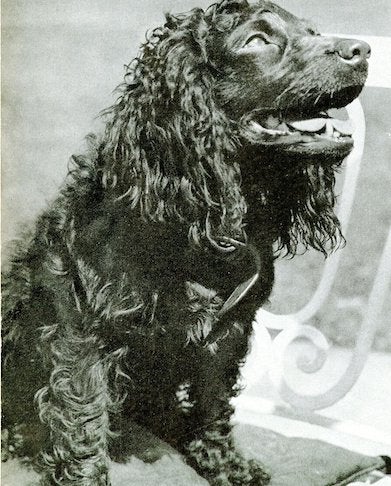

The dogs looked a bit like Field or American Water spaniels, but not quite, and they had glittering golden eyes and a can-do attitude that seemed just a tad, well, out of this world.

Dalmatian breeder and professional dog trainer Christine Prince noticed the little-brown-dog phenomenon when she moved from California to North Carolina in the early 1990s. “These dogs were everywhere,” she recalls.

Prince didn’t know it at the time, but she had stumbled upon the South’s best-kept secret, at least as far as dogs are concerned. Her new home was just one and a half hours away from the town of Camden, South Carolina, widely viewed as the fertile crescent for a unique American-made breed.

The ubiquitous little brown dog was South Carolina’s state canine—the Boykin Spaniel.

Swamp Creatures

South Carolina is predominantly a patchwork of lakes, rivers, and swamp forests, where tupelo and cypress trees grow straight out of the water, and the dryland spots—known as swamp hammocks—are covered with thick tangles of moss and plants.

Wild game birds—turkeys, ducks, quail, and doves—are abundant in these forests, but the hunting has never been easy. Getting around can most readily be accomplished by boat, the smaller the better. Most popular among the early hunters was a craft known as a “section boat.” As the name suggests, this boat was composed of three separate sections bolted together. Any one section could be used on its own, for navigating on water or setting up a blind. The boat could be taken apart, with sections nested for ground transport.

Hunters who traveled in these boats needed small, multitalented dogs who could find well-camouflaged game, flush it, then retrieve it and hop back into the boat. There was no way they could carry two dogs, or even one the size of a Labrador Retriever. A 60-pound dog would easily capsize a section boat, and their long legs would get tangled in the swamp hammocks.

So South Carolina hunters went about creating the perfect dog for their unique situation: versatile, hardworking, and “small enough to not rock the boat.”

Religious Experience

Odd as it may seem, the forefather of this extraordinary breed was a stray with the undignified name of Dumpy.

It all started somewhere around 1900, in Spartanburg, on a Sunday morning when Alec White, the president of a local bank, was strolling to morning service. Halfway there, a brown spaniel started to follow, and kept on his heels, right into church, where he was promptly ejected.

The cast-off canine waited patiently until the last “Praise the Lord,” and was wagging his tail in greeting when White appeared.

It was the beginning of a beautiful friendship. White named the dog Dumpy, and started to train him. The dog’s intelligence and versatility impressed his new owner, and, Creel notes, has fueled speculation that the stray was a performing dog who had run away from the circus.

White sent Dumpy off to a top trainer, Whit Boykin, of Camden, who established a new breed bearing his name. The Boykin Spaniel quickly became a favorite of local wild-turkey hunters, as popular in their geographic niche as Labrador Retrievers are in the rest of the country. But for decades, they were unheard of outside the region, kept under wraps by dedicated breeders who were very picky about who got their pups.

Greg Copeland, who now lives in Texas, about 60 miles from Houston, became interested in the breed on a hunting trip to Maryland in the early 1990s. Most of the group had Labrador and Chesapeake Bay retrievers, but there were some Boykins, and they stole the show. “The Labs and the Chessies had difficulties going through the tall grasses,” Copeland says. “These little dogs would go underneath, and invariably the Boykin would come in with the bird.”

It took great persistence for Copeland to get his first puppy. “We were out of the mainstream,” he recalls. “We looked high and low, but had a very difficult time getting anyone to sell one out of state. … Even in the mid-1990s, it was still a very closely guarded secret.”

Tiger in the Field

Many of today’s fanciers were introduced to the Boykin during trips down South from other parts of the country. Jim Kinnear, who hails from Connecticut, caught his first glimpse of one during a hunting trip in Birmingham, Alabama. There, a landowner gave him a pup in 1961.

He has had Boykins ever since.

“They are very, very sweet dogs, nice to have around the family,” Kinnear says. “On the other hand, they go through a total personality change when they get into the field. They are very avid hunters. It’s a combination of a dog that’s a pet around the house, but an absolute tiger in the field.”

He speaks with an awe bordering on reverence about one Boykin skill in particular, flushing. “With a Boykin,” he says, “you know the bird is going to be put in the air.”

Kinnear owns a game preserve in Clarksville, Virginia, where guests enjoy quail hunts with trained gundogs, usually a combination of pointing dogs and Boykins, for flushing and retrieving.

Today’s Boykin

The South Carolina Wildlife and Marine Resources Commission endorsed the Boykin Spaniel as South Carolina’s state dog in April 1984. On September 1 of that same year, Richard W. Riley, Governor of the State, proclaimed September 1, 1984, as Boykin Spaniel Day. Finally, South Carolinians made the Boykin Spaniel their official state dog in 1985 and continue to celebrate September 1 as Boykin Spaniel Day.

By 2009, the breed gained full AKC recognition, joining the elite assembly of the AKC’s “all-American” dog breeds.

There is a saying among fanciers that goes like this: “The Boykin is a hunting dog that can’t be spoiled by a mother’s love.” Unlike some breeds developed for the field, Boykins make great housepets.

“You can take a Boykin dove hunting in the morning, and then you can have them home at night as a family dog,” Paisley Lyne Stevens says. “They are very versatile.”

Stevens, former president of the Boykin Spaniel Club and Breeders Association of America (BSCBAA), grew up in Maryland with Basset Hounds, foxhounds, and a Vizsla. She moved to South Carolina about 30 years ago, where she first noticed all the little brown dogs. As a mother, what attracted her to the breed was portability. “They’re small,” she says. “It’s easy to have a dog in one hand and a kid in another.”

Other attractions include easy grooming—fanciers describe them as “wash and wear” dogs—and strong constitutions. It is not unusual for a Boykin to live 15 years or more, with some making it to 17. They have few inherited conditions, with hip dysplasia the most common.

But it’s their brains and personality that captivate most people. “They have a unique vitality,” says Stevens. “As puppies, they’re just ready. They’re born ready.”

Their quick minds allow them to adapt with ease to any task, whether it’s hunting, helping children learn to read, tracking wounded game, or comforting the sick. For this, they seem to have an inborn talent, as Patricia Watts, founder of the BSCBAA, learned in the early 1990s, when she was stricken with a serious neurological condition similar to multiple sclerosis. She was enrolled in a study of a chemotherapy drug that kept her bedridden for two years.