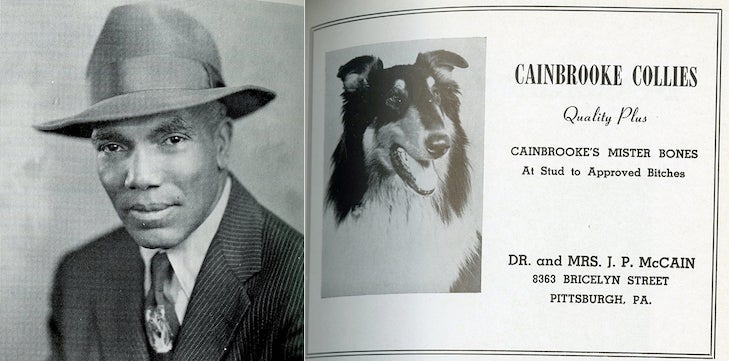

According to a friend, Dr. James Price McCain started exhibiting dogs in the 1930s to “relieve the nervous tension of his medical practice and perhaps most of all to participate in an activity in which his success or failure would be determined in merit, not solely upon the color of his skin.”

Dr. McCain’s merit is without question: he was regarded as one of the foremost Collie breeders and experts in all of dogdom, and a wise and generous mentor to many a show ring aspirant. He was first highlighted in the AKC Gazette in 1933 as “a truly dyed-in-the-wool collieite,” who joined the parent club in 1936. His “strong and well-argued” opinions, ranging from the flaws in the breed standard to the definition of good sportsmanship, were published and circulated amongst the fancy.

Cainebrooke Kennels, which he ran alongside his wife Gertrude, held the breed’s top-producing dam record for over three decades. By the late 1940s, he was an AKC-approved all-breed judge whose services were recruited all across the country. Only two weeks before his premature death from cancer in 1956, he awarded Best in Show at the Buffalo Kennel Club in a job, reported by the Gazette, “done as usual with care and competence.”

Remembering the First Black AKC Judge

This Black History Month, the AKC tips its hat to the first person of color to serve as an official AKC judge, who persevered with courage and commitment in show rings where no one else looked like him, in a pre-Civil Rights America that was frequently inhospitable. When Edwin J. Meyers wrote of his friend three decades after his death, he discussed his race, a topic unaddressed in his original obituary. He admitted that McCain was almost discouraged to give up, deferring to “the right-colored handler on the other end of the lead,” until he was able to more firmly established his line of dogs.

It can be assumed that Dr. McCain persevered over great adversity in this quest for legitimacy, encountering bias both implicit and overt. Traveling the United States in the name of his passion, he may have struggled to even dine and board at the same places as his peers. The local African-American papers in his home base of Pittsburgh proudly published accounts of the exploits and triumphs of this trailblazer for their community, writing “There is no doubt whatsoever that he is the outstanding Negro in the country of dog and dog life.” All came together to mourn him at his funeral, where four fellow Collie men served as pallbearers.

In the absence of Dr. McCain’s own account of his doggy experiences, his obituary, which first appeared in the Collie breed column of the AKC Gazette, is reprinted below. It is written with palpable affection by Edwin J. Meyers, who purchased his first show entry from the McCains. He recalled that Dr. McCain introduced him to the concept of Collie “type,” talking dogs “incessantly, or rather, he talked and I drank in Collie lore like a sponge soaking up spilled champagne.” Together they traveled the world six times over, befriending outstanding breeders and exhibitors, establishing a friendship he still cherished decades later, when in 1986 he established a Collie national specialty trophy in Dr. McCain’s name.

***

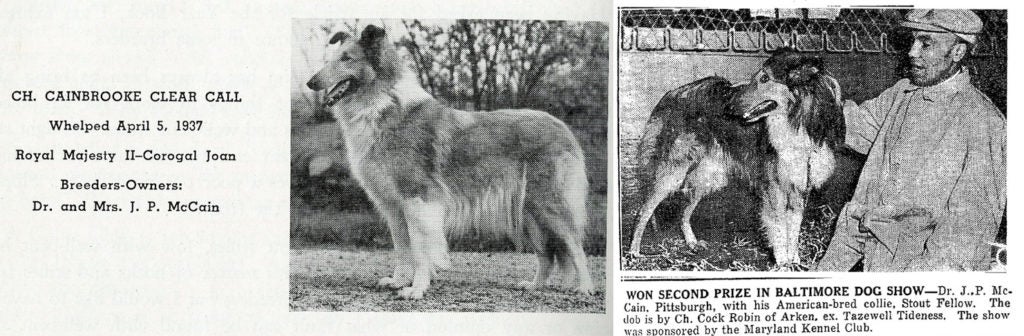

When Dr. James Price McCain died in the Pittsburgh Hospital on April 27, 1957 at the age of 64, the Collie fancy lost one of its staunchest supporters. Twenty-one champions have carried the Cainbrooke prefix—16 of them Collies. Among the most famous Collies were Ch. Cainbrooke Clear Call (the dam of seven champions), Ch. Cainbrooke Commodore, Ch. Cainbrooke Colonel, Ch. Cainbrooke’s Miss Tazewell, Ch. Cainbrookc’s Honey Chile, Ch. Cainbrooke “C-Note”, Ch.’ Cainbrooke’s Mr. Bones, and Ch. Cainbrooke’s Tomorrow.

For the past 12 years, “Doc” has been a tower of strength in the affairs of the Collie Club of America, Inc., serving the Parent Club in many important capacities. At the time of his death, he was the club’s first vice president.

Although his services were in great demand as a Collie judge from coast to coast and although he held the distinction of having, single-handedly, judged the largest Parent Club Specialty ever held (the California Collie Clan show—247 Collies), “Doc” will unquestionably be remembered most for his unfailing interest in the novice. If all the Collie fanciers of today, whose interest was stimulated and nourished by Dr. McCain, were to assemble in one room we would find a most distinguished group of Collie folk—all of whom would be anxious to be the first to acknowledge their personal debt of gratitude to this great and humble man.

The son of- a Methodist minister, “Doc” was a deeply religious man who practiced his genuine Christian philosophy as he practiced medicine; unostentatiously, painstakingly, effectively. He was born in North Carolina in 1892, was graduated from Livingstone College, founded by the great educator James Price for whom he was named. Later he was graduated from Howard University Medical School, married Gertrude Walker in Washington, D. C., interned at Freedman’s Hospital there.

He had lived in Pittsburgh since 1920. He was a charter member of Chi Delta Nu Medical Society, a member of the AME Zion Church of Pittsburgh, and a past-president of the Collie Club of Western Pennsylvania. Interment was at Homewood Cemetery, Pittsburgh, and since Collies represented one of the most vital interests of his life, four of the active pallbearers were longstanding Collie friends, Earle Polle, Robert Merker, Charles McClure, and Edwin Myers, all of whom owe their present Collie activities to his original interest in them as potential fanciers. Among the honorary pallbearers were such outstanding Collie personalities as William H. Schwinger, Charles H. Kay, and Alex Gibbs.

Dr. McCain is survived by his wife, Gertrude, his mother, Mrs. Julia McCain of Southern Pines, North Carolina, and his sister Mary of Mt. Vernon, New York. His death was caused by intestinal cancer and fortunately, he was spared any prolonged period of deep pain. It was the way he had said he always wanted to go—peacefully, in his sleep. In talking with him the day before his death, he made it clear to me that he had diagnosed his own case and said that if metastasis had not been too extensive, he would survive the operation. But if it proved to be too late, he said, “That will be all right, too.”

He had lived a full life. He was prepared to embark on a journey to another strange horizon. He mentioned that wherever his future ticket might read, up or down, he felt sure that among our good friends, […] he would find some way to welcome me into the hereafter with whatever reasonable facsimile of a Collie specialty show that it was possible to arrange when the Great Conductor picked up my ticket. So he died as he had lived, with a deep humility, an abiding faith in the future and a twinkle in his eye for the foibles of the present. Goodbye, Dr. McCain, I’ll try to have a puppy ready for your Hereafter Futurity.

All images and excerpts from the collections of the AKC Library & Archives.