To understand just how respected Ellsworth Gamble was, let us eavesdrop at a 1967 dinner where the legendary judge gave a speech to the members of the Kerry Blue Terrier Club of Northern California. Gamble stood to address the assembled fanciers whose dogs he had judged earlier that day.

Though he was a slight man, Gamble nonetheless commanded attention. Maybe it was his perfect posture or his patrician bearing. Or perhaps the intensity of his gaze, which never missed a detail of the dog before him. Or the purposefulness of his gestures, his hands demonstrating exactly what he thought of the dog beneath them. Whatever it was, the room was silent as the Kerry folk awaited the platitudes that never came.

“Ten years ago, when I judged the Kerries here, I said that I felt that the quality had declined,” Gamble reportedly said. “Now, ten years later, I can honestly say that the quality of Kerries is even worse.”

Amid the stunned silence, the revered judge retook his seat.

An Unexpected Outcome

The telling thing about Ellsworth Gamble was not that he had the conviction to stand before a room of the nation’s foremost Kerry breeders and point out their shortcomings, but rather that even after that stinging rebuke, he was still invited to attend and speak at club dinners. Now, that’s respect.

The son of a Scotsman in the foreign service who married an East Indian, Gamble grew up in Ohio and was a paratrooper during World War II. He was discharged from military service in the early 1940s after a Jeep accident left him with injuries so severe he was given just six months to live.

Ever pragmatic, Gamble decided that the company of a dog would help see him through his final days. Visiting Ohio State, where he had been a student before entering the service, he left with the gift of an Irish Terrier puppy from his former dean. There were even arrangements made to ship the dog back once its master was no more. Man and dog then headed to the West Coast, with Gamble determined to spend the little time he thought he had left enjoying the sunshine and his puppy’s high-jinks.

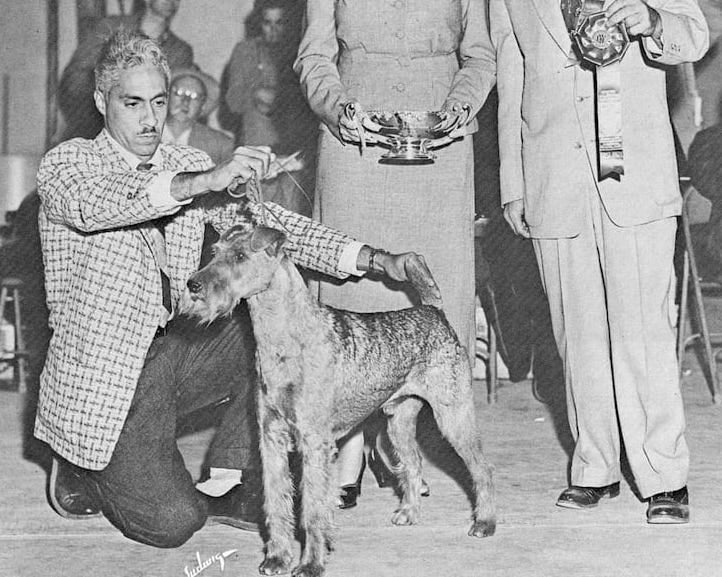

In defiance of medical predictions, Gamble not only far outlived his prognosis, but by the end of the year he entered his dog at the Golden Gate shows in San Francisco, leading to equally unexpected results.

“It was the first time in the ring for either of us, and we walked out with the Best of Breed rosette,” Gamble explained in a 1975 New York Times profile.

Exceeding Expectations

His death sentence commuted, Gamble found himself to be a talented handler. So adept was Gamble at presenting his canine charge that he consistently beat the professionals against whom he competed. In short order, he was hired to manage the Battle Hill kennel of Grace Reis, showing her Smooth and Wire Fox Terriers and doing the same for three nearby kennels that bred Kerry Blues, and Standard and Miniature Schnauzers, respectively.

Branching out from terriers in the late 1940s, Gamble presented dogs for some of the highest-profile kennels on the West Coast, including Kay Finch’s Crown Crest Afghan Hounds. But it was as a judge that Gamble became best-known. After hanging up his show lead in 1964, he soon earned a reputation as a no-nonsense arbiter who did not hesitate to withhold ribbons on dogs he considered lacking in quality. Conversely, he was well-known for rewarding deserving puppies with top honors, even at high-profile shows where other, less confident judges might have been tempted to reflexively point to the big winner of the day.

A Style All His Own

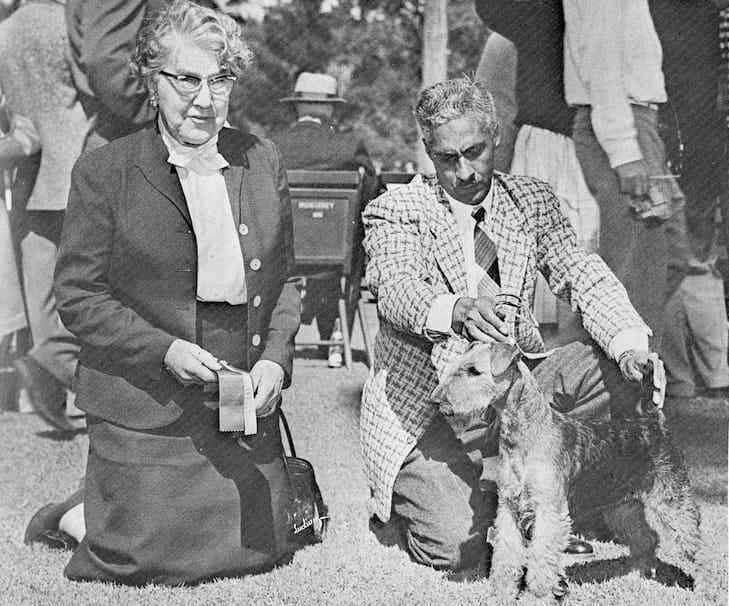

Afghan Hound fancier and well-known judge Michael Canalizo first encountered Gamble as a preteen with just a few years in the sport. Even as a youngster, Canalizo knew there was something different about the man who moved his long, lithe hands so deliberately and swiftly over the dogs he examined in the ring. Silently appraising, with no time for banter, Gamble had a ring craft that Canalizo remembers to this day.

“Just watching his hands told me a story,” Canalizo recalls, adding that Gamble’s intensity was palpable. “Once he touched the dog, his hands never left the dog’s body. They literally went from head to toe in one complete motion. Once he did the exam, you were instructed to move down the mat, and you had to ‘stop.’ You were directed to turn left, and ‘stop.’ Then you turned left once more … and ‘stopped.'”

In a later interview, Gamble explained the logic behind his personal ring procedure.

“As a former professional handler, there isn’t anything they can do to fool me, whether it’s dyeing, faking, or holding a dog up, because I make them take the dog out and stand it all four sides standing free and don’t touch it,” Gamble said. “So, it’s up to the dog. There’s nothing [the handler] can do except hold the end of the lead.”

Many years later, Canalizo asked Gamble why he was so inclined to put puppies up for the highest awards.

“He carefully explained that he felt the younger generation was vital to moving a breed forward in a positive way,” remembers Canalizo, who himself has a reputation for awarding worthy youngsters, thanks to his mentor’s wise words. “Many foundation breeders of that generation hung their collective hats on his evaluation of their dogs.”

Judged To Be Worthy

In truth, however, it took some years for the dog fancy to steel itself for Gamble’s unvarnished opinion. In the late 1940s, while still a handler, he accepted two judging assignments at specialty shows, which was permitted in those days. At the first, he asked for a microphone in lieu of a fee, and after broadcasting a critique on each of his Collie placements, quipped that “there was only one person who was there that day who will even speak to me to this day.”

The second was a Chow Chow specialty where Gamble gave the breed to a young, typey unknown, passing over a big winner.

“When I gave my reasons, why, they wouldn’t believe me,” Gamble recalled years later about the much-hyped loser. “So I stuck my finger on the dog, just one finger to prove the point.”

The champion literally fell down.

Not surprisingly, Gamble had strong feelings on any number of subjects, including the superfluousness of Group and Best in Show competition (“Personally, I think the judging stops with the breed”); the reality of politics in the ring (“I still cling to my early-formed ideas that there must be a certain amount of collusion somewhere for some dogs to win”), and the dispensability of professionals (“All handlers would be unemployed if all the dogs were good, because no one would need a handler”).

To be sure, not everyone appreciated such unflinching honesty. Unlike the Kerry Blue example that started this story, Gamble said he wasn’t invited or spoken to after his comments at some specialties. But most who entered his ring did so with a mix of acceptance and respect.

The Gifted Gamble

“Even the most competitive handlers deep down would admit Mr. Gamble had a gift,” Canalizo says. “And many times those very handlers were not unwrapping any presents when in his ring.”

Staying beneath that blinking holiday tree for a moment, if there was anything Gamble discounted, it was what he called “tinsel” – distracting and ultimately meaningless aspects such as flashy handling and furious ringside clapping. Instead, he focused relentlessly on type and those unique qualities that separate one breed from another.

“You know, each breed has its own individualities. I would like to learn more about these finer points,” Gamble said toward the end of his judging career, taking that metaphor about seeing the forest for the trees to an altogether new level. “I couldn’t care less about the tinsel.”