In the early 1950s, a stunning Doberman Pinscher came charging out of California to vanquish the best show dogs the East Coast elites had to offer. In the process, he became an international superstar.

Among the treasures of the AKC Library & Archives is the Len and Shirley Carey collection of photos, clippings, scrapbooks, correspondence, and ephemera, donated by the Doberman Pinscher Club of America, concerning one of America’s all-time great show dogs: Ch. Rancho Dobe’s Storm. In 1952 and 1953, the Careys’ magnificent Doberman Pinscher owned the Westminster Kennel Club’s big green carpet at Madison Square Garden, going Best in Show back-to-back in those years. (You might say Westminster Best in Show was in Storm’s blood: His great-grandsire was Geraldine Rockefeller Dodge’s Ch. Ferry von Rauhfelsen of Giralda, 1939’s Best in Show winner.) As one of only seven champions to earn multiple Bests in Show since Westminster first gave the award in 1907, Storm remains an undisputed legend of the sport of dogs.

Storm was born in 1949 and came to the Careys at 2 months old from his breeders in Van Nuys, California. He lived with Len and Shirley, and their son, Jeff, in their swanky Manhattan apartment before the family relocated to Connecticut. At 4 months, Storm was entrusted to professional handler Peter Knoop.

Storm was judged best Doberman at his very first show, and he took Best in Show his second time out. Early on, the Careys’ and Knoop realized that in Storm they had a once-in-a-lifetime dog. “Like any show dog, Storm had some points that could have been better,” Knoop said, “but all things considered, soundness, elegance, personality, he was unbeatable.”

The Rivals

The most colorful artifact in the Carey collection is a framed display of Storm’s 17 Best in Show rosettes. (The two Westminster rosettes command pride of place, top row center.) During his brief career, Storm was exhibited at just 25 shows. He never lost to a dog of his own breed, and he won the Working Group 22 times.

Winning the Working Group at Westminster, or any dog show, in the 1950s was an impressive feat. Before 1983, the AKC Herding Group did not exist. All working breeds and all herding breeds were shown in the Working Group, meaning that Storm was competing in the group ring against such perennially popular show dogs as Old English Sheepdogs, German Shepherd Dogs, and Pembroke Welsh Corgis, in addition to Working Group mainstays like Great Danes and Boxers. It was quite a feat for any dog to make it out of the crowded pre-1983 Working Group and into the Best in Show ring’s final six.

Storm’s record is even more impressive considering his career coincided with that of superstar Boxer Ch. Bang Away of Sirrah Crest, who dominated the Working Group on his way to a then-record 121 Bests in Show. “Boxer fanciers around the world still pay homage to the role this extraordinary dog played in the development of the modern Boxer,” Patricia Trotter wrote in the AKC Gazette. “With his tremendous body type and flashiness, he was ahead of his time and represented the future of his breed in every respect.” The first California-bred dog to go Best in Show at Westminster, Bang Away was a true coast-to-coast sensation and the show ring’s first crossover media star of the TV era.

Storm met his archrival and fellow Californian just six times in Working Group rings. Storm won the group ribbon in four of those head-to-head matchups. Their most famous meeting came at Westminster, 1952. Bang Away entered the show as defending champion, having gone Best at the Garden the previous year. Storm bested the great Boxer in the group and went on to his first Westminster Best in Show.

Life magazine reported, “During the final judging, Storm stood motionless for thirteen full minutes while the judge [Joseph Sims] looked over the field of six. As Storm held his pose—few human beings, let alone dogs, can stand still for thirteen minutes—the eyes of one onlooker after another swung to him and remained fixed, until at last 12,000 people were staring breathlessly at him. Finally, Sims approached him, and at that instant Storm turned his head, peered puckishly up at the judge, then resumed the pose. The crowd gave one prolonged roar, and kept on roaring until Sims signaled that Storm had won the show.”

The Real Don Draper?

Len Carey, who served as a Marine captain in World War II, was a high-powered advertising executive, said to be among the real-life models for the fictional characters of TV’s “Mad Men.” He was a Californian who relocated to New York when his firm, Batton, Barton, Durstine and Osborn, landed the lucrative Lucky Strike cigarette account. Cigarette advertising has long since been banned from all media, but in the mid-20th century gaining or losing a big tobacco account could make or break an ad agency.

Carey was a happily married family man and respected dog fancier and judge, in temperament nothing like his hard-drinking, womanizing counterpart on “Mad Men,” Don Draper. There were, though, many distinct similarities: Both Carey and the fictional Draper were war veterans from California who came east to Madison Avenue and wound up managing the all-important Lucky Strike account. Also like Draper, Carey married an elegant woman who prided herself on being the perfect hostess. The Careys’ handsome suburban home was a showplace, and even the regal Storm was required to have his feet wiped before entering. Interestingly, they lived in Cos Cob, Connecticut, a town featured prominently in several “Mad Men” episodes.

After Storm’s repeat win at Westminster in 1953, the sleek 93-pound Dobie was such a celebrity that Carey was able to mix business with pleasure by featuring his wife and his dog in Lucky Strike ads. The photo above of Shirley Carey and Storm was one of several taken for the campaign.

Immortal

Storm’s second consecutive Westminster win, in 1953, was a controversial choice among the Garden faithful. “Storm won on soundness,” judge James Farrell told the Associated Press, defending his selection. “He was sound as a bell.” Knoop added, “I think he handled better this year than ever before, even last year when he won.”

The second Westminster win clinched Storm’s entry into the pantheon of the all-time greats and brought him the kind of international fame that even Bang Away would envy, assuming for a moment that dogs were capable of such human pettiness.

With TV still in its infancy, newsreel films were still a popular news source. Two different newsreels about Storm’s exploits were filmed and shown in movie theaters around the world. A CBS film crew was dispatched to Cos Cob to shoot an up-close-and-personal profile of Storm. (Shirley Carey told CBS they couldn’t enter her meticulously kept home unless they brought help to clean up the house afterward. They did.)

Storm was the subject of a full-length profile in Life magazine, the first time that immensely popular publication ever accorded the honor to an animal. Other leading magazines followed suit. Newspapers from coast to coast featured Storm on page one, some even published editorials in his honor. Royal Doulton, Britain’s premier maker of porcelain figures, did a brisk trade in a statuette of Storm. It went on sale at the peak of Storm’s fame for $17.50. It remained a popular item in the Doulton catalog for 30 years. Today, fanciers of both Doulton and Dobies will pay in the $100 to $200 range for these prized collectibles.

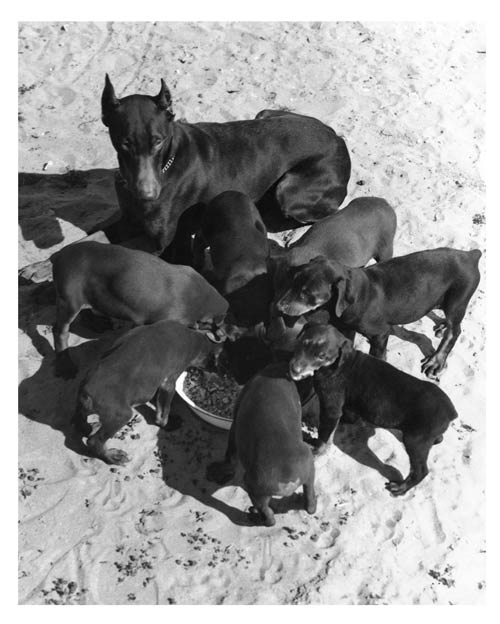

It was as a stud dog that Storm gained his most important hold on immortality. After the Westminster wins, with nothing left to prove in the show ring, Len Carey put Storm out to pasture (“He’s earned his rest,” the doting owner said), where he lived like a retired king. Storm’s stud fee was raised to a princely $150 dollars, and he spent the remainder of his 11 years siring scores of puppies—including many ring champions. To this day, the sight of the name Ch. Rancho Dobe’s Storm in a pedigree is enough to excite the imagination of any true Doberman fancier.