More than 8,000 feet above sea level in the year 1050, snowdrifts would blow as high as 40 feet across a crucial passageway in the Alps. This important path, where pilgrims made their way to Rome, was treacherous to cross due to these conditions. That’s when a monk named Bernard of Menthon (later canonized) decided to create a hospice that would aid pilgrims who were journeying to Rome — Hospice of St. Bernard.

But rescuing hundreds of tired travelers wasn’t a one-monk job. What happened when these weary journeyers became victims of avalanches, unconscious and trapped below deep drifts of snow? That’s where the mighty Saint Bernard came in.

Early Roots of the Saint Bernard

Saint Bernard-type dogs were present in the region now known as Switzerland since ancient times. The Germanic tribes who inhabited the area and periodically raided the Roman Empire used their canine giants as war dogs. Even the most battle-tested Roman legions were said to quail before these fearsome, four-legged goliaths.

The Romans, of course, had their own dog of war: the ferocious Asian Molosser. Breed historians posit that the Saint Bernard’s 1,600-hundred-year march to the AKC Working Group began when Molossers were bred to the native giants of the Alpine valleys in the first two centuries AD.

The Rescue Dogs of Monks

Oliver Goldsmith wrote of Switzerland’s monks in the early 1700s: “They have a breed of noble dogs whose extraordinary sagacity often enables them to rescue the traveler. Though the perishing man lie 10 or even 20 feet beneath the snow, the delicacy of smell with which [the dogs] can trace him offers a chance of escape.”

The most famous of these rescue dogs was Barry, a Saint Bernard who worked at the Hospice of St. Bernard, a refuge for pilgrims crossing the treacherous passes of the Swiss Alps on their way to Rome. Between 1800 and 1814, Barry saved 40 human lives.

Although the hospice monks were training Saints for rescue work long before Barry’s time, it was the legendary Barry who cemented the Saint’s worldwide reputation as Alpine rescue dog supreme. So great was Barry’s renown that his name became synonymous with the breed: An old Swiss moniker for the Saint was “Barryhund.”

No Casks of Brandy Around Their Necks

Here’s some news: the original rescue dogs of the St. Bernard Pass didn’t wear little casks of brandy around their necks.

In 1820, a 17-year-old British artist named Edwin Landseer had his first great success with a painting titled “Alpine Mastiffs Reanimating a Distressed Traveler.” The huge canvas depicts an unconscious avalanche victim. Surrounding him are two Saints. One barks for help as the other licks the traveler’s hand in an attempt to revive him.

From one of the dog collars hangs a cask, a whimsical detail wholly invented by Landseer just to add a little something to his picture. (Surely the hospice monks, with long experience in Alpine rescue, knew the debilitating effect of alcohol on those suffering from hypothermia.) Landseer’s stroke of inspiration caught the public’s fancy, and the brandy cask became the enduring symbol of the Saint Bernard.

The boy artist went on to become Sir Edwin Henry Landseer, RA, England’s peerless painter of canine themes, and Queen Victoria’s favorite artist. And Saint owners today still adorn their dogs’ collars with casks on special occasions—but it was the Saint’s amiable good nature, not brandy, that warmed the hearts of weary travelers.

A Breed in Trouble

As a breed, the Saint Bernard was in a sorry state by the turn of the 20th century.

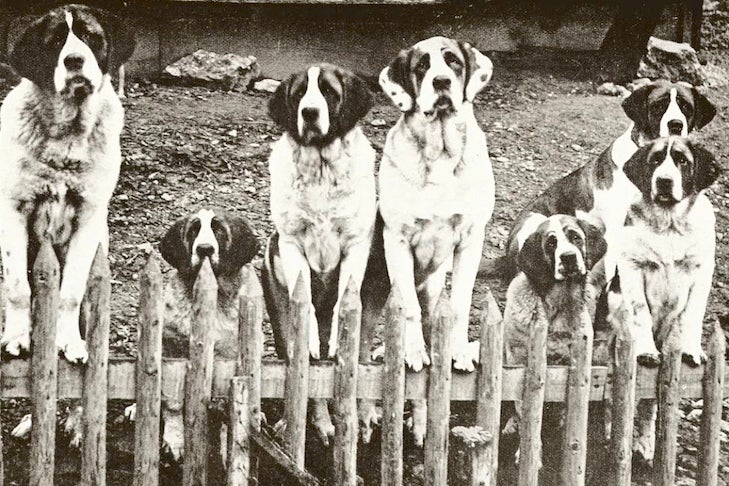

“The breed has changed remarkably since my grandparents’ day,” Janice Holmes Myers says. Myers operates the Massachusetts-based Carmen Kennels, the nation’s oldest registered kennel. She’s a third-generation breeder whose grandmother was showing Saints in the early 1900s.

“In the family scrapbooks are photos of Sea View Abbess. She was the dog of the day. But look at the picture: She’s practically swaybacked! If you trotted her out today, they’d laugh you out of the ring.”

U.S. fanciers of the early 20th century made it their mission to return the Saint to its former glory. Good Saints still existed, and breeders looked to these dogs as their templates of breed type. One such dog was a British ring champion named Frandley Stephanie, seen above in Maud Earl’s famous painting “I Hear a Voice.”

A dog-show judge of the era wrote that if breeders would use Stephanie as their guide, “they will soon bring Saint Bernards back to the position they once held in public estimation.” By mid-century, after generations of judicious breeding of domestic stock and imports, Saints once again looked like Saints.

Entering Pop Culture: Beethoven

Today, most people associate Saint Bernards with the wildly popular “Beethoven”, but that wasn’t always the case.

In the film, the kids really want to keep the adorable stray puppy who wandered into their tidy suburban home. The fastidious Newton—after several choruses of “Please, Dad, please, can we keep him?”—finally relents, only to watch in horror as the little fuzz ball grows into 200 pounds of slobbering, shedding Saint Bernard.

Critics dismissed “Beethoven” as a throwback to the kiddie-matinee fodder ground out by Disney in the 1960s and ’70s. But despite tepid reviews “Beethoven” made sweet music at the box office, to the tune of a combined $110 million gross for the film and its hit sequel.

Producer Ivan Reitman, riding a hot streak that included “Stripes” and “Ghostbusters,” shrewdly crafted “Beethoven” as critic-proof entertainment guaranteed to be, as Hollywood publicists like to proclaim, “fun for the whole family!” Reitman commissioned a script from John (“Ferris Bueller’s Day Off”) Hughes sufficiently silly for kids but sharp enough for grownups, and then assembled a cast of expert farceurs led by Charles Grodin, using the same quirky, deadpan delivery that upstaged Robert DeNiro in “Midnight Run.”

The chief selling point of “Beethoven,” though, was Beethoven. There hadn’t been a Saint Bernard pop-culture star since the “Topper” TV series of the 1950s, and audiences were ready to renew their fascination with this magnificent breed. For a few years in the early ’90s, drool was once again cool.