Anyone foolhardy enough to be outdoors in Le Harve, France, on a stormy, windswept evening in October 1789 would have beheld a curious sight: a conspicuously tall, ginger-haired gentleman striding through a soaking rain, urgently searching for something he apparently held quite precious.

Onlookers in the old port city might have wondered if he was looking for a missing child, or perhaps a lost purse of gold coins. What else would bring out this unfortunate wretch in such foul weather? For Thomas Jefferson, celebrated author of the Declaration of Independence and noted dog hater, the unlikely answer was sheepdogs. In particular: the Briard.

Thomas Jefferson’s Journey to Shepherd Dogs

In a letter he wrote to his assistant back home in Virginia, Jefferson explained: “I was yesterday roving thro the neighborhood of this place to try to get a pair of shepherd’s dogs. We walked 10 miles, clambering the cliffs in quest of the shepherds, during the most furious tempest of wind and rain I was ever in. The journey was fruitless.”

Jefferson had recently concluded his long tenure as American minister to France. He was in Le Harve with his two daughters and with James and Sally Hemings, enslaved people, to board the ship that would carry them home. He had dearly hoped to depart with a breeding pair of the local shepherd dogs in his entourage.

As his political enemies knew all too well, the “Sage of Monticello” was not an easy man to discourage. The day after his misadventure in the rain, the same day his ship sailed for America, Jefferson found the object of his quest. He made this entry in his memorandum book: “pd. for a chienne bergere big with pup, 36 libre.”

Bergère, as the bitch “big with pup” was named, whelped two offspring during the transatlantic voyage. These herding dogs that Jefferson prized so highly were the chiens bergeres de Brie, the large, shaggy dogs now known as Briards.

French Boundary Herders

Related to other French flock dogs in the AKC Herding Group, like the Beauceron and Pyrenean Shepherd, Briards have roamed the pastures of France since the reign of Charlemagne in the eighth century. The breed is even named for the dairy-producing region of Brie, best known for the gooey cheese of the same name.

French farmers, known for frugality, developed Briards as two-in-one dogs: They are sheepherders famed for quicksilver agility, and are also tough, courageous flock guardians capable of running off sheep-steeling predators like wolves.

Closely related to the smooth-coated Beauceron, another French pasture breed known for its dual herding and guarding ability. the Briard was a robust working dog.

While in most countries, the Briard and Beauceron are in the herding group, they are not traditional herders, such as Border Collies or drovers such as Old English Sheepdogs. They had a different role: boundary herders. This means that their job was to keep the sheep within the boundaries and more importantly, to keep thieves and other predators, such as wolves, out.

This helps explain why these two herding breeds have erect ears. Ears that point up help the dogs hear predators better and are less prone to injury and infection. Both the Beauceron and Briard breed standards allow for either natural or cropped ears.

Wool, War, and Dogs

By early 1790 in the United States, Thomas Jefferson assumed the job of America’s first Secretary of State and Bergère and her two pups were comfortably ensconced at his beloved Monticello. Oddly, considering the pains that Jefferson took to acquire them, there was little work for his sheepdogs to do. You see, there were very few sheep at Monticello.

During America’s years as a British colony, American farmers lived under the Wool Act. This draconian law prohibited the export of wool from the colonies and levied a stiff tax on sales of woolen goods. Meant to tilt the balance of trade in favor of the mother country, the law all but stifled the wool industry in colonial America. As a result, Americans had little reason to keep large flocks of sheep.

By the time Jefferson returned from France, the American Revolution was won and the fledgling nation’s Constitution was ratified. Jefferson wisely foresaw that the newly independent America would soon have a booming wool industry of its own. When that happened, he would have a head start on breeding world-class sheep-herding dogs, thanks to his French imports. But Jefferson, as always, was thinking beyond the short term. He was intent on creating a perfect agrarian society at Monticello, one that would stand as the model for his countrymen long after he was gone. (That this utopia was built on slave labor was, and remains, a bitter irony of the Jefferson story.)

Jefferson was an inveterate collector and list maker. During his long sojourn in France, he compiled lists of the best Europe had to offer—books, wines, foods, trees, and animals included. He was determined to transport as many of these things as possible to the paradise he was building at Monticello. When it came to dogs, Jefferson took his cue from the great French naturalist the Comte de Buffon, whom he greatly admired. According to Buffon, the Briard was the smartest and most industrious of all European dogs.

“Bergère’s employment was secondary to her role as founder of the American branch of her family,” a Monticello historian wrote. “The shepherd’s dog was on Jefferson’s list of Old World animal species worthy of ‘colonizing’ to the United States, along with the skylark, nightingale, and red-legged partridge, the hare and Angora rabbit, and the Angora goat.”

The Dog Man of Monticello

Unlike his fellow Virginian and revolutionist George Washington, who was passionately devoted to breeding foxhounds, Jefferson wasn’t what you would call a “dog guy” by nature. In fact, he once wrote that he would be agreeable to exterminating the entire canine race.

But during Jefferson’s climb from secretary of state to vice president and finally to president, the Monticello sheep population grew to include many head of Merino and Barbarry. As the owner of such valuable flocks, Jefferson came to appreciate the value of a good herding dog. Bergère’s working ability became something of a Monticello legend, and Jefferson wrote that her multiplying offspring were “all remarkably quiet, faithful, and abounding in the good qualities of the old bitch.”

Over the years Jefferson imported more of the French herders. One pair was sent by none other than the great Revolutionary hero the Marquis de Lafayette. In 1813 an appreciative Jefferson wrote to his old friend in Paris, “The Shepherd dogs mentioned in your of May 20 arrived safely, have been carefully multiplied, and are spreading in this and the neighborhood states where the increase of our sheep is greatly attended to.”

Indeed, as wool production became a factor in America’s burgeoning economy, requests for Briard pups came to Monticello from as far afield as Kentucky. In his post-presidential years, when he wasn’t occupied with founding the University of Virginia, Jefferson was busy fielding puppy inquiries.

“There are so many applications for them that there are never any on hand, unless kept on purpose,” he wrote one disappointed seeker. Then the man who once said dogs were the “most afflicting of all the follies for which men tax themselves” added a sentence indicating that, in the end, his Briards had won his heart: “Their extraordinary sagacity renders them extremely valuable, capable of being taught almost any duty that may be required of them, and the most anxious in the performance of that duty, the most watchful and faithful of all servants.”

Everyone Loves a Briard

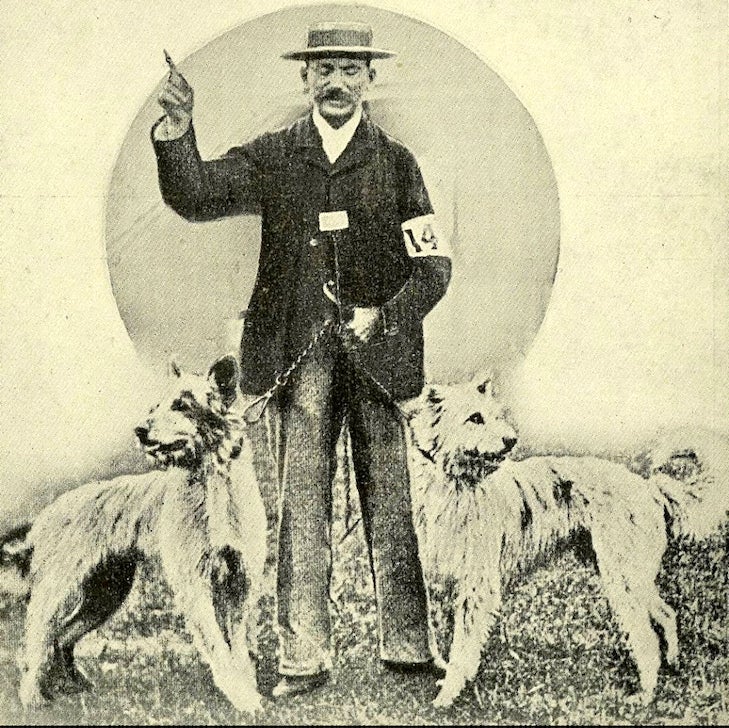

By the 1800s, the Briard was a cherished both in the United States and France. Even Napoleon, who had an aversion to dogs, was said to be a fan of the breed. The Briard was proudly exhibited at the very first French dog show, at Paris in 1865. By the time of World War I, the Briard was so much a part of the national character that it was named the official war dog of the French army, doing sentry duty, finding wounded soldiers, and pulling supply carts.

The American Kennel Club officially recognized the Briard in 1928. Today, the Briard is among the less popular herding dogs — ranking 150th out of all 195 breeds. But those who know and love the Briard worldwide continue to echo the words of Jefferson, praising the remarkable working dogs.