Isn’t it always best to get a dog from its country of origin? I mean, you can’t get more authentic than a German Shepherd Dog from Germany, or an Italian Greyhound from Italy, or a Chinese Shar-Pei from China – right?

Well, not so fast. That answer is highly breed dependent. And in the case of the Boerboel, getting a dog from its native South Africa can be fraught with difficulty – for reasons that have to do with much more than mere logistics.

Origins of the Boerboel

First, some history, murky as it might be: The Boerboel (pronounced “boo-r-bull”) is South Africa’s answer to the Mastiff. The breed’s origins are right there in its name: The Boers are the descendants of Dutch colonists who settled in Africa’s southernmost tip in the late 1600s. “Boer” means farmer, and “boel,” loosely translated, is a large dog, like a mastiff.

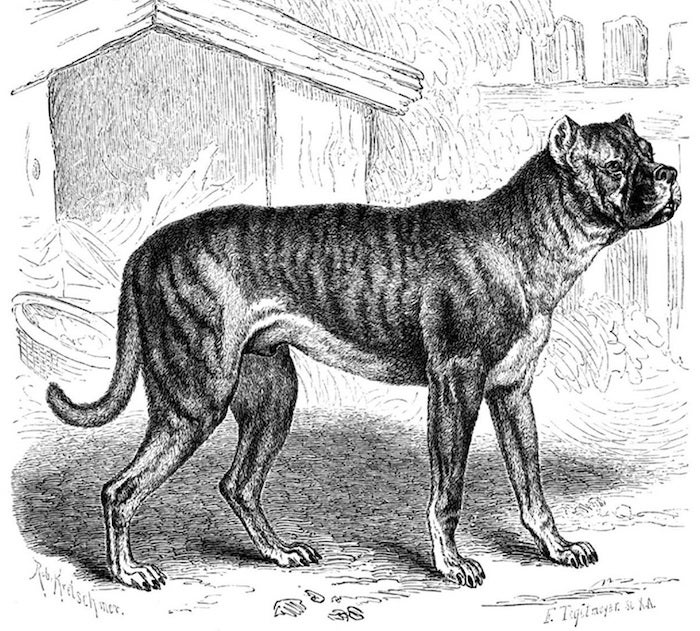

Some of the Boerboel’s ancestors came with the first European settlers in southern Africa: When Jan van Riebeeck arrived in 1652 to work for the tea company that founded the Dutch colony at the Cape of Good Hope, he brought along a Bullenbeisser – literally, “biter of bulls” – a now-extinct breed believed to have been involved in the development of the Boxer as well. Centuries later, DeBeers imported some of Britain’s finest Bullmastiffs to patrol its famous diamond mines. And even the most fleeting glimpse of a Boerboel reveals the Bullmastiff influence in terms of the large, blocky head, tremendous bone and traditionally seen colors and patterns (fawn, red and brindle).

These Bullmastiff imports from the 1920s, along with longer-legged Bulldogs brought into the country by the British, helped solidify the Boerboel’s appearance, which is best understood by its degree of “bulldogginess.” Boerboels are bullier than Bullmastiffs (whose own breed formula is said to be 60 percent Mastiff and 40 percent Bulldog) but less so than the Dogue de Bordeaux, whose upsweep of chin and front-loaded weight distribution are even closer to Bulldog type.

All-Purpose Protection Dog

Despite all this talk of Bulldogs, the Boerboel was bred to be an incredibly athletic animal. Life in South Africa was physically taxing and frequently dangerous for humans and dogs alike. Both the Boerboel and its distant cousin the Rhodesian Ridgeback had to be all-purpose dogs, though the Boerboel was more a protection dog that could be called on to hunt, and the Ridgeback just the reverse.

The two breeds went on very different trajectories not because of the jobs they did, but rather the individuals who championed them. The Ridgeback headed north to British-controlled Rhodesia, where in the 1920s interested fanciers took up the cause of standardizing the breed. But back in South Africa, Boer farmers – less inclined than the British to whip up a breed standard over tea biscuits and watercress sandwiches – were more focused on using the Boerboel to guard their farms and families.

As with many breeds bred for protection, the Boerboel can be intolerant of strangers. And, traditionally, the breed is also not wild about canines of the same sex. Concerns over aggression have resulted in the Boerboel being banned in some countries, such as Denmark and Singapore, though the breed is famed for being a doting nanny of the children in its family circle. While any breed can have its share of unsocialized and poorly controlled dogs, the sheer size and power of the Boerboel make it all the more important that it be extensively socialized. This is not a breed for an inexperienced or weak-willed owner.

Standardizing and Recognizing the Boerboel

The Boerboel was such a reflexive part of Boer farm life in South Africa that in previous centuries having a standard was almost superfluous: Dogs that survived the rigors of the bush and did their job well went on to procreate; the rest … well, didn’t. It wasn’t until the early 1980s that a movement to organize the Boerboel as a bona-fide breed was undertaken in South Africa.

In the United States, interest in the Boerboel skyrocketed rather early, and in the 21st Century this once-obscure breed zoomed through the AKC ranks: Added to the AKC’s Foundation Stock Service – the first step toward official recognition – in 2006, the Boerboel joined the Miscellaneous Group in 2010 and went on to full AKC recognition in 2015.

That popularity, however, also had a dark side: Some Boerboel breeders, realizing that uneducated American buyers would pay a premium for “rare,” historically incorrect colors such as black, began to produce such dogs, presumably through crosses with black Labs or Neapolitan Mastiffs. Not surprisingly, these unconventional colors caused chaos in the breed, leading to the fracturing of breed clubs and widespread disagreement about how to handle the incursion of foreign blood.

Despite the vigorous objections of the Kennel Union of South Africa, the proponents of black Boerboels gained legal control of the breed in its native land. This created an impasse that essentially means the Boerboel in its current state will likely never be recognized by the Féderation Cynologique Internationale, under whose auspices most dog shows in non-English-speaking countries are held.

Today’s U.S. Boerboel

In the United States, however, the breed was already recognized, and the American Boerboel Club lost no time in making its unequivocal position on these aberrantly colored dogs abundantly clear: The AKC standard disqualifies them because they are not among the breed’s accepted base colors or patterns, which are red, brown, reddish brown, fawn, cream, brindle in any accepted color and Irish marked.

The club took an additional step to protect the integrity of its pedigrees: Imported dogs whose pedigrees contain any Boerboel documented to have produced black dogs cannot be registered with the American Kennel Club.

Given that reputable and ethical Boerboel breeders now exist all over the world, one does not have to go to South Africa to acquire a typey, healthy, stable example of the breed. But if you do decide to make that transatlantic purchase, be sure to have the pedigree reviewed by the American Boerboel Club beforehand. If not, you might find yourself with a dog who cannot be shown or registered with the American Kennel Club – a real misfortune in a breed this rare and still in the earliest stages of recognition.