Curiosity didn’t just kill the cat. It did in the duck, too.

Over the centuries, bird hunters have come up with creative ways to close in on their quacking prey, in part by breeding specific dogs to help in that endeavor. Centuries ago, hunters in the Netherlands came up with perhaps the most outside-the-box idea for a bird-hunting breed – by watching, of all things, foxes.

Over millennia, those clever wild canids have realized that ducks are fascinated by novelty, and learned to use that insatiable curiosity against them. Gamboling near the water, the fox plays with a stick or other object, studiously ignoring the mesmerized ducks that slowly paddle to the shoreline to survey the commotion. As long as the fox doesn’t face the ducks and trigger their flight reflex, the hapless birds slowly drift closer and closer until… Well, you can guess the end of the story.

The Little Dog With a Big Name

Inspired by this vulpine artifice, in the 1500s, perhaps even earlier, Dutch hunters created the Nederlandse Kooikerhondje. Pronounced “Netherlands-e Coy-ker-hond-tsje” – if that’s too overwhelming, try Kooiker (“koy-ker”) for short – this little dog with the big name was bred to look like a fox, with its orange-and-white coat, well-feathered tail, and handy size. In these centuries before firearms were invented, hunters used bows and arrows, snares, or nets to secure their duck dinner. Having a dog that could take a page out of the fox’s playbook and trick the birds into waddling toward their own demise was an inspired solution.

If this job description sounds a lot like that of a North American breed, the Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever, that’s no coincidence. Tollers are believed to have descended from Kooikers.

Capitalizing on these unique geographic conditions, the Dutch developed an elaborate duck-hunting system focused on an enclosure called an eendenkooi, which translates as “duck cage.” In fact, the English word “decoy” – from the Dutch de kooi, or “the cage” – derives from this centuries-old hunting technique.

Trapping Wild Ducks

In a country as small as the Netherlands, the eendenkooi is a surprisingly large piece of land of at least a couple of acres, its perimeter ringed with ample vegetation to provide nesting places and act as a buffer against any human activity in the area. In the center is a pond with several “pipes,” or offshoots. Seen from the air, this configuration looks like a rounded letter “H,” in which the center bar is enlarged and curved like a tick, representing the pond.

The goal of the duck hunter, or kooiker, is to get the ducks to swim up one of these pipes – the gently curved vertical lines of our imaginary letter H – which are chosen on any given day based on the way the wind is blowing. The sides of the pipe are flanked by reed mats, behind which the kooiker can stay hidden and assess the goings-on. At the end of each net-covered pipe is a trap box.

Getting the wild ducks into the pipe and eventually the trap box is the job of the Nederlandse Kooikerhondje. Sometimes, the dog is aided by a group of semi-tame “decoy” ducks that have been conditioned to swim into the pipes to obtain food. At the direction of the hunter, the dog trots the length of the screen, weaving in and out, the flashes of their white markings intriguing the wild ducks, which then swim farther into the pipe.

For a job this complex and precise, the Nederlandse Kooikerhondje had to be extremely intelligent and responsive to the hunter’s body language and hand signals. During the ducks’ breeding season, the breed was also called on to be a ratter, helping rid the eendenkooi of vermin.

Was the Kooiker Almost Lost?

With their spaniel-like proportions and pleasing, friendly expressions framed by ears with fringed “earrings” of black fur, the Nederlandse Kooikerhondje soon became a valued companion as well, depicted in paintings by early modern Dutch masters such as Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Steen. A Nederlandse Kooikerhondje supposedly saved the life of Prince Wilhelm the Silent in 1572 by rousing him in his army tent to warn of an impending attack by Spanish assassins. (Some sources claim the dog was a Pug.)

By the 17th century, the Netherlands was home to some 3,000 duck-trapping eendenkoois. Today, only a hundred or so remain, mostly used to capture and band birds for research, after which they are released.

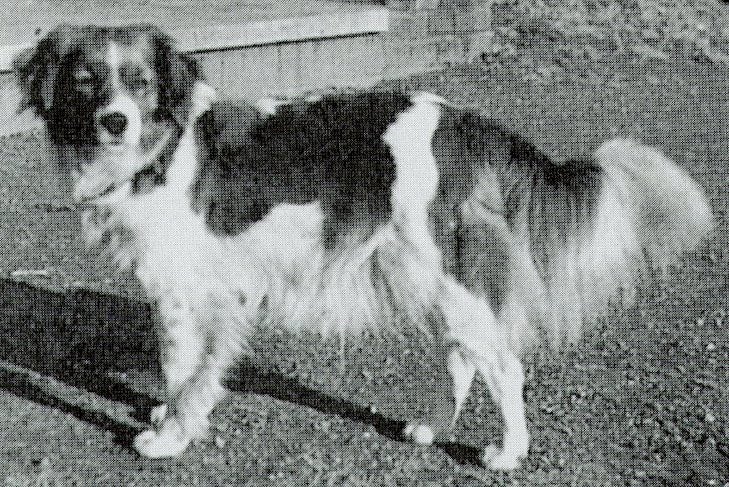

The Nederlandse Kooikerhondje had experienced a similar nosedive in popularity by the early 20th century, surviving largely due to Baroness van Hardenbroek van Ammerstol. Entrusting a peddler with a photo and lock of hair from a Kooiker, she had him scour the countryside for any remnants of the breed. In this way, the baroness acquired “Tommy,” the female on whom the modern breed was reconstructed. The baroness bred her first litters during the war, and by the 1970s, the breed had regained sufficient numbers to be recognized by the Dutch Kennel Club.

Even then, the Kooiker was not recognized by the Fédération Cynologique Internationale – sort of Europe’s answer to the American Kennel Club – until 1990. And the breed’s formal recognition in the United States did not come until just recently, in 2018.

Today’s Kooikers

Today, while there are thousands of Kooikers living in the Netherlands, the breed isn’t as overwhelmingly popular in North America. But it’s a good bet that once American dog lovers get a glimpse of this charming breed – not unlike the glints of white and flashes of movement of the hard-working dogs around the reed screens of the eendenkooi – they’ll want to know more.