Four decades have passed since the dawn of New York’s poop-scoop law. Has it changed the world?

In 2019, a Denver homeowner posted a sign on her lawn. It was a cry of frustration, her version of “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take it anymore.”

Unlike the insane newscaster from the movie Network, her anger wasn’t aimed at corporate greed or the sad lot of old broadcasters.

Dog poop had driven her to a white-hot rage and she vented on a bright orange sign.

“These are the kinds of inconsiderate [expletive] that should never own or walk dogs,” reads the opening salvo. It then offers a menu of “dog deterrence” methods—like setting out traps and/or smearing excrement on perpetrator’s doors.

Neighbors and online commentators called her a monster and spewed threats of violence if she harmed a pet.

But a reporter who caught up with the homeowner found a different side. The woman insisted her fury wasn’t directed at the animals—she loved and had owned dogs in the past —but at their humans, who had been using her property as a doggie toilet for years.

Her reaction was intense, but by no means unique. Few daily issues have the power to make someone crazy like the question of when and where other people’s dogs do their business.

“Dogs are sacred cows,” says Alan Beck, director of the Center for the Human-Animal Bond at Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine, in West Lafayette, Indiana. To many, they are family, he says, and even mild criticism seems a violent personal attack. On the flip side, dog critics feel “personally violated by someone else’s dirt. It’s somehow an insult.”

Dog droppings have played a role in some bizarre acts of vandalism (see sidebar), stalking, fistfights, and even murder.

In one strange case in Dallas, for example, a man shot his wife after her German Shepherd Dog fouled the kitchen.

“Sometimes it’s just a trivial little thing that sets people off,” a police officer observed.

Minefields and Dung Heaps

In the 1970s, Beck had a front seat at one of the nastiest battles ever waged over the matter—the campaign to persuade New York City’s canine-loving set to pick up after their dogs.

It split the city, Beck says, into “two warring camps, those who loved dogs and those who hated those who loved dogs.”

The city was struggling, out of cash, and riddled with crime. Its streets, once fabled for being paved with gold, were encrusted with dog waste, an estimated 500,000 pounds of it a day.

Trendsetters that they are, New Yorkers came up with a novel solution—New York State Public Health Law 1310, formally known as the Canine Waste Law.

Or, as it’s affectionately called today, the “Poop Scoop Law.”

Beck, then head of New York’s newly created Bureau of Animal Affairs, says the law was not the first. That distinction goes to Nutley, New Jersey, which started cracking down on this quality of life issue in 1971.

Why was a law needed? After World War II cultural changes brought an influx of dogs to cities—first as companions, then as guards against rising urban crime.

No one really gave much advance thought about how to handle the waste problem.

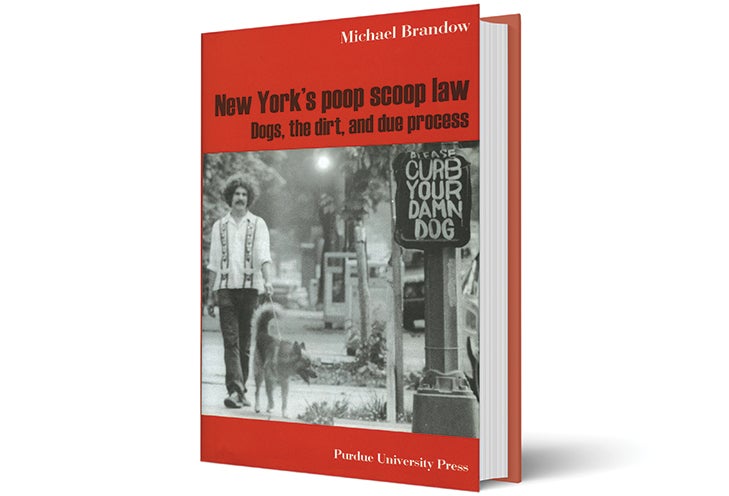

At the time, the assumption—a carryover from horse and buggy days—was that sanitation workers would take care of things, wrote Michael Brandow in his 2006 book New York’s Poop Scoop Law: Dogs, the Dirt, and Due Process.

City officials tried different approaches, like a short-lived doggie toilet. Later the “Curb Your Dog” campaign required pets to do their business in the gutters so sanitation workers could flush it away each day. But the idea turned out to be impractical and too expensive.

Putting the responsibility on owners seemed the logical solution, but the idea sparked indignation, even horror.

On the other side were people who felt dogs did not belong in urban spaces. Fran Lee, outspoken leader of the militant Children Before Dogs group, wanted them all out; barring that, at least that they be required to relieve themselves in the privacy of their owners’ homes. For her opinions, she was heckled, threatened, and pelted with feces.

It took years of political, legal, and cultural turmoil, but in August 1978, the law went into effect and became a prototype for similar legislation all over the world.

Scoop Shaming

Critics scoffed, in part because enforcement would require a dedicated squad of poop police, something no city could afford.

Critics scoffed, in part because enforcement would require a dedicated squad of poop police, something no city could afford.

But Beck says it wasn’t all about fines, but cultural change, similar to efforts that made buckling a seatbelt into a reflex. Dog owners had to be made to understand that keeping the streets clean could convince even the most hardened foe of animals to accept a fuzzy neighbor.

To achieve this, Beck says, the city created a public relations campaign aimed at transforming the revolting task of plucking feces from the ground into a badge of honor, a sign that you care about the environment, and the harmony, comfort, and health of your community.

Such laws sparked a shift from “not my job” to “my civic duty.” Today, dog walkers shame those who leave a mess behind, often by running up to the offender and “helpfully” offering a bag.

A recent study (see sidebar), showed that about 97 percent of dog owners said they believed people should clean up after their pets. Only 3 percent said it was not their responsibility.

Even people who could reasonably be expected to get a pass try to conform.

Michelle Barlak, spokeswoman for The Seeing Eye, in Morristown, New Jersey, says people who are blind are exempt from scooper laws in most places, but her organization still prepares teams to follow the rules.

“We teach our dogs to stand in one place while pottying so that they are easier to clean up after,” she says. “A dog that circles while it eliminates will be rejected from our program if that habit cannot be changed. It’s really important to us that our graduates clean up after their dogs so that they leave a positive impression on their community.”

Sweep Smell of Success

The day before New York’s law went into effect in 1978, panicked dog owners flocked to stores in search of a strange, newfangled device, the “pooper scooper,” Brandow wrote. “Stores ran out of all items within a few hours, and people still lined up on the sidewalk went home terrified at the thought that, come the next morning, they’d be left holding the bag.”

Overnight, a humiliating burden became a marketing opportunity.

Inventors had been patenting dog-refuse disposal units since at least the 1960s. The first designs were simple—foldable cardboard boxes or stick-mounted metal containers with an attached rake.

The no-frills era didn’t last long. Today you can find products to suit any style, whether you prefer standing tall and clamping down with aluminum jaws, sucking it up with a battery-powered vacuum, or freezing it with a stool solidifying aerosol. One design features a harness that places the bag strategically on the dog’s rear.

New professions have sprouted up around this once lowly task. One is the dung detective, who uses DNA to put the finger on law-breaking dog owners. Another is the professional poop scooper, for whom there is a trade group with about 100 members—the Association of Professional Animal Waste Specialists. At their annual convention, practitioners show off their skills in “turd herding” contests.

Toymakers also leaped in, with such offerings as the “Barbie Walk and Potty Pup,” giving the iconic doll a scoop so she can clean up tiny plastic droppings left by her retriever.

Even the humble plastic bag—traditionally a supermarket castoff—has gone upscale, with floral and ocean breeze scents, bright colors, cute designs, corporate logos, and custom shapes.

Perhaps nothing illustrates the elevated status of scooping more than the rise of fashionable poop bag holders.

Once no-frills plastic cylinders to hang on a leash, these items now come in fanciful shapes and fancy styles, some that look like tiny purses and cost $100 or more.

For a time—it has since been discontinued—the online Posh Puppy Boutique offered a “Clear Bone Crystal Poop Bag Holder” covered with 2,000 hand-set Swarovski crystals. The cost of this must-have for the poop-plucking fashionista—$480.

Originally ran in the May/June 2019 issue of AKC Family Dog.