Rolissa Nash has been fighting her whole life for equality in and out of the show ring.

Rolissa Nash was born in 1950 — a premature baby wedged halfway between a century. At only four pounds, 11 ounces, her difficult birth was just the beginning of her lifelong health struggles, and only one of the many setbacks she would face. She was also Black child born into a world where Jim Crow was prominent and segregation was at its height.

As an only child in Coney Island, Rolissa had an insatiable curiosity. By six, she was checking books out of the library on every topic she could think of. That’s when she found the library’s one and only book on official AKC dog training. Rolissa’s mom sat with her, reading the book and explaining how different Obedience skills worked.

Most of Rolissa’s childhood was spent in and out of the hospital due to many medical issues including chronic asthma. Because of this, Rolissa’s only friend became her dog. First her terrier, then a Chihuahua, then several mixed breeds.

“I can’t even remember a time I never had a dog,” Rolissa said.

By her teens, Rolissa had been intubated numerous times. But that was only part of her trouble. At 15, her father died. And at 17, her mother died while Rolissa was talking to her in bed.

Rolissa called up a family friend: “Would you do me a favor?” she asked. “Please go to the police and tell them that my mother died.”

It took two days for the police to show up. Rolissa sat on the staircase waiting with the only thing she had left — her dog.

By the time the police took away her mother’s body, Rolissa began to replay her mom’s warning in her head over and over: “Whatever happens to me, I don’t want you to go to your uncle.” Rolissa didn’t understand. But as a minor, she needed to either be taken in by a family member or enter foster care.

That was the beginning of the section of Rolissa’s life she calls the belly of the beast.

People Are Cruel: The Sixties

“I realized people are cruel. People are heartless. People are confused,” Rolissa said of her late teens, when she lived with her abusive uncle.

At 18, Rolissa graduated high school and left her uncle behind. She was extremely smart – studying at and graduating from Columbia University, where she got married at 20 and had her only son at 21.

As a newlywed and new mother, Rolissa still longed for a dog in her life. Her husband Artis agreed to get a dog after researching the best breed for their family. They settled on a Samoyed, but getting a puppy as a Black couple proved to be difficult. Rolissa recalls making an effort at “sounding white” on the phone but having breeders turn her away once she showed up at their homes. Once they found a breeder who would sell them a puppy, Rolissa struggled to find a training center that would accept her.

Once Rolissa found both a dog and a training center, she decided she wanted to learn more about showing her dog in Conformation and Obedience.

“No, you can’t do that,” she was told. “There’s no place for you. It’s not available for you.”

Rolissa was used to being persistent — she had spent her whole life overcoming obstacles. So every day after work in Manhattan she would drive around the five boroughs and even into New Jersey looking for training centers that would welcome her and teach her.

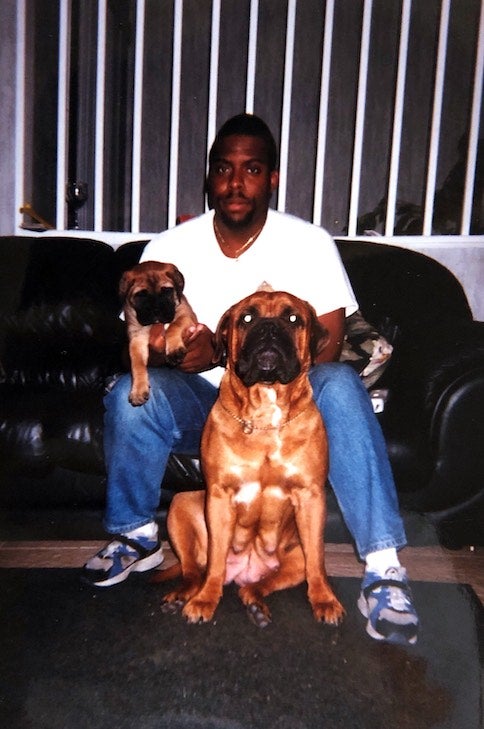

During Rolissa’s research on dog training, she became fascinated by a new breed and decided she wanted to pursue Bullmastiffs. But again, she discovered that her biggest roadblock to getting the dog she wanted was her skin color. “Once they found out I was Black, they didn’t want to sell me a Bullmastiff,” she said.

So again, Rolissa rolled up her sleeves. She did her pedigree research and found the lines she was interested in, which brought her all the way to upstate New York, near the Canadian border. This breeder had puppies sired by All Star Bullmastiffs, a huge name in the dog world in the ‘70s and ‘80s. All Star Bullmastiffs were known for winning big in AKC Conformation.

Rolissa brought home the puppy, continued training, and kept looking for training centers that would accept her. But no matter where she went, the response was almost always the same: “When I would walk in, the reaction of everyone was, to say the least, shock. I was a Black woman walking a Bullmastiff.”

A Black Woman With a Bullmastiff: The Seventies

The majority of people in Rolissa’s training classes had limited social exposure to Black people before. The same was true at Obedience competitions. But she realized that once fellow competitors saw she knew what she was doing in the ring, and she knew how to control her imposing dog, their attitudes changed. “The more people that got to know me, the more their reactions to me changed,” Rolissa said. “I don’t know if they got past my color, but I got past their judgement.”

At Rolissa’s first-ever dog show, she competed in Obedience at the Nassau Coliseum on Long Island. “I walked in with my Bullmastiff puppy, and everyone there literally started whispering and looking at me.”

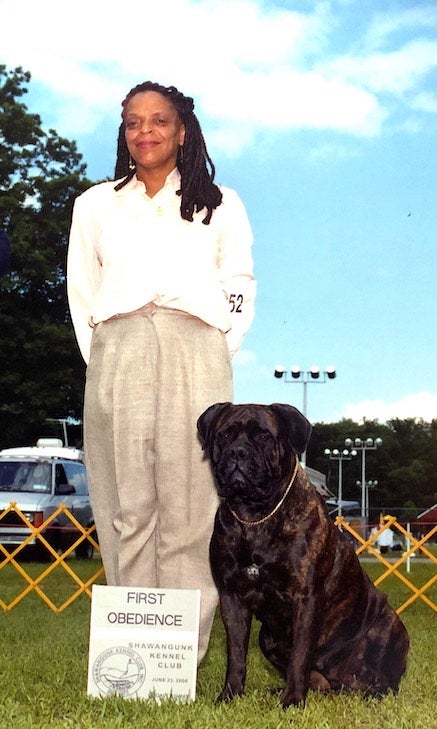

But Rolissa knew what she was doing. She won that Obedience competition. And when she won, people began approaching her. “What dog is this?” they asked, intrigued by the talented newcomer.

“It’s an All Star,” she would say. She was met with gasps. “How did you get an All Star?”

After her success in Obedience, Rolissa started training in Agility and Conformation. “I wanted to learn as much as I could because I owed my dog that. I owed them that because of what they have done for me my whole life.”

Before long, something happened to Rolissa that had never happened before at a dog show: someone showed her immediate kindness.

“Hi! How are you?” an excited woman asked, running up to Rolissa after a show. “I saw your dog, it was wonderful. You should come join our club!”

Rolissa smiled. “I wouldn’t mind that at all!” She wasn’t speechless. She just appreciated the fact that someone was so friendly.

That kickstarted a period of learning in Rolissa’s life. She joined as many clubs as she could, desperate to soak up knowledge. She volunteered, learned to steward, learned to judge conformation, and even started breeding.

Rolissa used her new knowledge as a jumping off point for her son, Myles. An intelligent boy, he went to a private school in the top 2 percent of all of New York City. Just like Rolissa’s mom did everything with her, Rolissa wanted something she could do with her son.

Myles soon loved the joy of winning dog shows. But the reality was that many times Rolissa and her son were placed last. The question was, were their dogs placing last, or were their handlers the only ones being judged?

I Know I’m Black

“You, stand over there in that corner,” some judges would mutter to Rolissa and Myles during dog shows. Rolissa never missed a beat, respecting the judges even when she felt disrespected.

When she and her son would lose, Rolissa would simply curtsy to the crowd and wave — her own form of pained acceptance. Others saw it as ignorance.

“Well, you’re not going to win. You know you’re not going to win,” people would repeat to her.

Rolissa chuckled. “If I don’t win, the audience is blind.” But Rolissa knew better than to cause a scene.

“If you want to stay, you learn to be quiet,” Rolissa said.

Even her closest friends would tell her, “Rolissa, you can’t win.”

“Why can’t I win?” Rolissa would retort.

“Because you’re Black.”

“I am? I’m Black? I didn’t realize that,” Rolissa would jokingly respond.

Her friends and her would laugh.

“I know I’m Black,” Rolissa would say. “But if I don’t do it, who’s going to do it? I love it.” She believed herself to be a trailblazer.

On trips to the Midwest and South, Rolissa’s husband would stay in the car. “I cannot go inside and watch. You’re going to places where there are no Blacks, Rolissa,” he said.

“But there are no Blacks anywhere,” Rolissa responded. At the time, Rolissa had never seen another Black person show a dog in Conformation.

“Never. Ever. Nowhere. Anytime. I would walk in places and they literally had their mouths hanging open. It was the strangest feeling, but I had an objective. The objective was to enjoy myself and to give back. Not just to give back to my dogs but to give back to me.”

Team USA: The Eighties

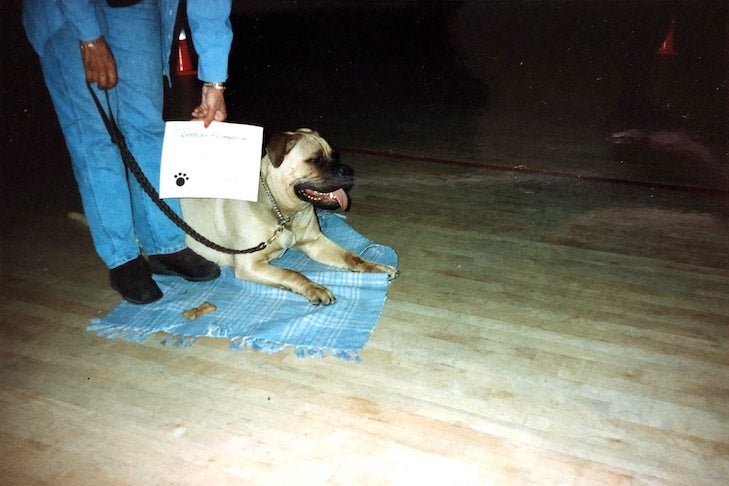

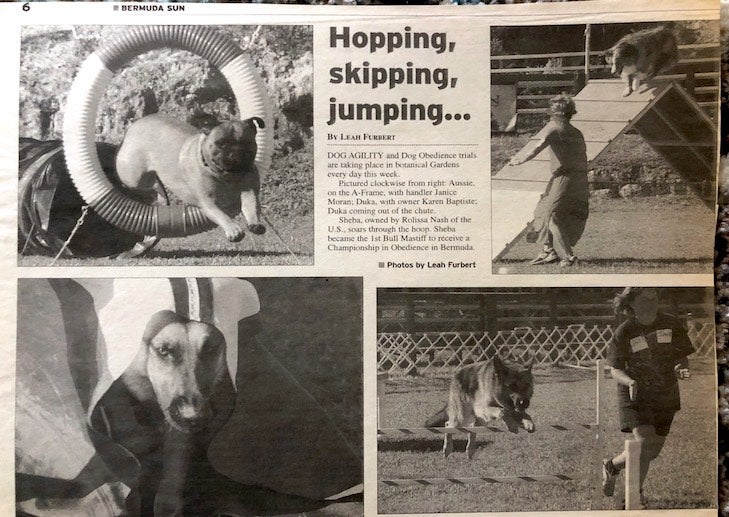

In the 1980s, it took two years of planning for Rolissa to travel to Bermuda as part of Team USA to compete in Agility, Obedience, and more. At the time, Bermuda didn’t allow any dogs bigger than a Boxer in the country, so they had to arrange special permissions for Rolissa and her Bullmastiff to compete.

But getting off the airplane, Rolissa knew something was wrong. Outside, someone was trying to steal her Bullmastiff, Charles, on the tarmac. Scared, Charles began sprinting around between airplanes. Security told Rolissa she couldn’t set foot on the tarmac, but Rolissa had other plans. “Gentlemen, please. You’re going to have to arrest me because I cannot leave my dog running out there with planes.”

Charles immediately ran to Rolissa, but he was covered in scrapes and cuts. The whole airport was shut down until they could get an emergency vet to come.

That was the beginning of the pressure Rolissa felt in Bermuda. Newspapers all over the area covered her arrival, fixated on the fact that a giant Bullmastiff was visiting. People from all over came to support Rolissa and her dog Charles. And even though she expected to see other Black people in Bermuda, she was still the only one competing.

When it was time for Charles and Rolissa to run Agility, Charles was still recovering from the injuries he sustained during the airport incident. “Ok, let’s go, Charles,” Rolissa said. But Charles wouldn’t run.

That’s when the giant crowd started chanting his name. “CHAR-LES! CHAR-LES!” they roared. Rolissa took a deep breath. Okay. This is only as serious as I make it.

“Come on boy! We can do it Charles!”

As the crowd continues to chant his name, Charles’ tail started whipping.

Rolissa felt a rush of joy. Charles took one jump. One. And the crowd went wild. The clock was running, but the judge didn’t take them off the course. Charles slowly went from one jump to another, the crowd screaming his name the whole time.

“I don’t know how long it took, but when it was over the crowd was bonkers.” Rolissa said, recalling a rare moment of pure bliss. “It was just the best thing in my life. Support by a community of dog people.”

Actor and producer Michael Douglas was in the crowd, and he came up to Rolissa after the performance. “I’ve heard so much about you. And I heard what happened. We came out to support you.”

For once, Rolissa felt that moment with her dog transcended her Blackness. “I became just a woman with her dog that’s been injured, who is trying to get her dog back on track. And that’s when we felt the love.”

Don’t Let This Define You: The Nineties

Rolissa’s childhood illnesses never went away. When she wasn’t in the hospital, she would muster up the strength to compete. Some years stretched on in a pattern alternating between dog shows and hospital stays. She soldiered on.

Sometimes, she would show under judges who were alleged to be associated with the KKK.

“Why are you showing to this person?” her dog friends would ask her. “They’re never going to put you up. Don’t you know that? They’re always going to make you last.”

“Well, then they’re always going to make me last,” Rolissa would reply. “I’m not going to withdraw my entry because to withdraw my entry means that I’m defeated. I’m doing this because I love it.”

“Get a handler,” they would tell her. By that time, everyone recognized Rolissa’s dogs and how well trained and in shape they were, so would hiring a non-Black professional handler even matter, she wondered? But Rolissa loved showing her own dog. Sure, maybe she could win more often if she hired a professional handler. But for what?

“I refuse to get a professional handler,” Rolissa told her friends. “If I’m not doing this myself then who am I doing this for? Who am I doing this for?”

While she never hired a professional handler, she did have a crew of dog friends always on call to help her show her dogs if her medical issues kept her sidelined.

It wasn’t until the early ‘90s that Rolissa saw another Black woman competing in the show ring. A few years later, at the Bullmastiff National, a group of Black people came in with about 20 gorgeous Bullmastiffs. They didn’t win anything. Not their class, not a placement. Nothing.

“Don’t let this define you,” Rolissa told them, encouraging them to stick with it. “If you keep coming and you don’t get bitter, you will win. But you have to keep coming out. You have to keep pushing forward to get the respect you deserve. If you leave, they’ve won.”

That was the first and last time Rolissa ever saw them.

The Birth of Doggie U: The 2000s

Around the year 2000, Rolissa began helping people ringside here and there, giving them tips on how to show their dogs. Then she started teaching people in earnest, and realized she had a real talent for it. That was the beginning of Doggie U K9 Academy.

Around the year 2000, Rolissa began helping people ringside here and there, giving them tips on how to show their dogs. Then she started teaching people in earnest, and realized she had a real talent for it. That was the beginning of Doggie U K9 Academy.

Rolissa opened Doggie U K9 Academy in 2004. She was still working full time in Manhattan and would drive straight to the facility on Long Island in the evenings after work.

“I went from one dog club on Long Island to another,” Rolissa said. “I knew all these people from shows. I would say ‘Hi, I’m here for you. I just wanted to tell you I’m opening Doggie U. It’s space for you to show your dog and develop your dog. I’m having an open house and want everyone to come out.”

At that first open house, only one club showed up – the local Afghan Hound club.

“Why isn’t anyone here? This place is fantastic!” members of the Afghan club remarked.

In her mind, Rolissa wanted to tell them it was because she was Black, but she held her tongue. “I’m glad you’re here. I really am here to help you.”

For a nominal fee, the Afghan Hound club held a show at Doggie U to raise money, kickstarting official club competitions at her facility.

But just as things were looking up for Rolissa and Doggie U, her husband Artis died from health effects arising from the of September 11 attacks. In his case, it was cancer. While Rolissa had been sick all her life, he had never been ill. The sickness destroyed him and his subsequent death weakened her.

Then, in a year of seemingly unending bad luck, Doggie U flooded.

Every person on Long Island who came to Doggie U showed up in galoshes. The ceiling was collapsed, walls crumbled in, and still people came out to help Rolissa salvage as much equipment as they could.

To keep Doggie U going, Rolissa held classes in the parking lot. Once she had enough money, she moved to a new location, installed top-of-the-line foam flooring, and eventually got things back and running again.

She opened up her first official Conformation class at the first location of Doggie U, and her students came back show after show, telling her they won. Hearing their comments, Rolissa would think back with fondness at her own favorite instructor, Janet Bunce.

“All of a sudden I got a reputation of having an eye for showing,” Rolissa said. “So I would work on strengthening dogs, developing dogs and their owners to their best, so when they walk the ring, the judge would say ‘That’s a nice dog. A very nice dog. And a skilled handler.’”

But shortly after reopening, Rolissa’s kidneys started failing. She focused on her dogs. For five years straight Rolissa was in stage five kidney failure. Despite her worsening condition, she continued showing. Sometimes she would show up in the ring wearing a leopard-print suit. Or a bright pink hat to cover her hair.

She would stride into the ring confidently, then collapse back in her hotel room when the day was done. Friends would walk her dogs because she was only strong enough to compete once each day. “No one knew how sick I was,” Rolissa said.

By her fifth year of kidney failure, she was really struggling. Once, she passed out in the conformation ring. “Oh, I just forgot to eat,” she fibbed to the judge as she stood up and continued to show her dog. She would go back to her hotel room and look at herself in the mirror, repeating: “I can do this. I can do this. I can do this because this is what’s keeping me alive.”

She made it through to transplant surgery, receiving her son’s kidney. To this day, doctors are in disbelief when they learn she never had dialysis.

Above Water: The 2010s

In a cruel bout of repetition, a water main break outside of Doggie U flooded the entire facility in the middle of a show—again. Sixteen inches of water filled the facility as competitors scrambled to evacuate dogs and move equipment on top of crates and out to cars.

That moment stuck with Rolissa. “No matter what, even the color of my skin, these are the friends that have been built up through competition, through being there for them and them being there for me. The love that is generated from a dog transcends no matter what the color of my skin is.”

Rolissa hired a cleanup crew and the facility was back up and running in less than a month. It was a setback in time and money, but Rolissa — and the community — were relieved to have their facility back.

Years passed and countless handlers, including professional handlers, would send their clients to Rolissa.

Doggie U became the largest training facility in the New York metropolitan area. It’s also the first and only Black-owned indoor training facility licensed to hold AKC trials in the United States. Most importantly, it became an important hub of community.

“If you speak to many clubs on Long Island, they will tell you, ‘Because of Rolissa and Doggie U, we are both in existence.’ But it took 15 years to get to that level.”

2020: Can Doggie U Survive?

In 2020, Rolissa hit another roadblock: COVID-19. “I’m trying to reinvent Doggie U,” Rolissa said. “But I’ve reached the point when somebody could help me besides the clubs — my dog family.”

It was hard for Rolissa to admit she needs help. She pulled herself through life by her bootstraps for 70 years. In rare moments of emotion, Rolissa let out a few tears, overwhelmed by the thought of losing her facility, everything she has worked toward. During the pandemic, she did everything in her power to keep the facility and community alive. She scheduled private lessons at all times of day and night, even meeting clients at 11 p.m. to keep students safe and to keep the facility up and running.

People who have used the facility lament to her, “Rolissa, you have to stay open, because without you, our club will be gone.”

Every club on Long Island has been invited to or uses Doggie U as a venue.

“Deep in my heart of hearts, I hope that we reached a time in our life where someone could step forward and see my vision and help bring us forward into the future,” Rolissa said. “When I’m gone, my hope is that Doggie U will still be there to help our AKC community.”

Of everything Rolissa has accomplished in life and been through, she continues to put her community ahead of herself.

“I want someone to know when I’m gone that Doggie U was here for them. Doggie U was here for their dogs. Doggie U was here for all those people that need hope or need a dream, not the color of our skin. We are a reflection of our dogs.”

Rolissa would do anything to keep Doggie U alive. Although the pandemic took a huge toll on her, she continues to invest in the dog community — teaching children, mentoring teenagers, inspiring adults, and, of course, continuing to show her own dogs.

Just before the pandemic hit, Rolissa was surprised to find she was showing under a familiar judge. As she entered the ring, she did a double take. Yes, it was one of those judges who, in a different era, had put her in last place. So much had changed over the past 20 years, but Rolissa had never stopped showing up with confidence and pride. This time, without hesitation, he placed Rolissa first.

***

Rolissa needs help to continue helping the dog community through Doggie U K9 Academy. As the only Black-owned dog training facility at its level in the country, the future of the sport depends on diverse businesses like Rolissa’s. If you are able to, donate directly to Rolissa here: https://www.gofundme.com/f/keeping-doggie-u-k9-academy-open-for-our-dogs.