It is common knowledge that Anatolian Shepherd Dogs came to America to stay in the 1950s, imported by ranchers and working-dog aficionados. And it’s even better known that the Anatolian Shepherd Dog joined the AKC Working Group in 1999.

What is little known, however, is the fact that two Turkish flock-guarding dogs—thought to be Anatolians—were sent to Washington, D.C., in the late 1930s to take part in a top-secret government program. The stated objective: to find the world’s greatest sheepdog.

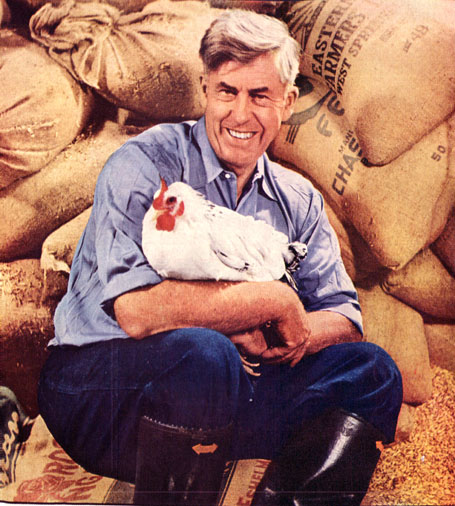

The story begins with Secretary of Agriculture (and future Vice President) Henry A. Wallace. The secretary was the scion of a prominent Iowa farm family and a proponent of “scientific agriculture.” Before coming to Washington to serve in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal cabinet, Wallace was a pioneer in the development of hybrid corn and large-scale chicken farming. “If you had eggs this morning, there is a good chance they came from a Wallace chicken,” Alex Ross wrote in a 2013 New Yorker profile. “Forty-four per cent of the world’s eggs are produced by hens that derive from the genetics of [Wallace’s] Hy-Line poultry stock.” (His heirs would eventually sell the family business to DuPont for $9.4 billion.)

Henry Wallace

Wallace’s interest in genetics extended beyond corn and chickens. A devoted dog lover, he was keenly interested in how canine intelligence was inherited over generations of breeding. As head of the Department of Agriculture, he was in a unique position to study the question. This was still Depression-era America, though, and he knew Congress would withhold appropriations for a study that promised no national economic benefit. But if he could somehow combine pure research with a practical application, funding would be assured. Thus was born the federal Sheep Dog Project.

The study was conducted at the Beltsville Research Station in Maryland, where Pulik, Border Collies, and other flock dogs were assembled for study. The mandate was to determine which breed made the best sheepdog. This, said Wallace, would be of great use to America’s wool industry. In these pre-WWII days mass-produced artificial fibers were unknown. Wool was king, and sheep ranchers comprised a large and powerful constituency. Wallace got his funding.

It was during the formative days of the project that Wallace attended a White House dinner and found himself seated beside the Turkish ambassador. He mentioned the Sheep Dog Project and the quest for the perfect sheepdog breed. The conversation went something like this:

Ambassador: “But that has already been determined. The best sheepdog is our Turkish sheepdog.”

Wallace: “I was not aware of the Turkish breed.”

Ambassador: “Perhaps that is because we consider them to be so valuable that we do not export them from Turkey. However, in the interest of science, which is international, perhaps I can arrange for a male and a female to be obtained for your project.”

It was the kind of Washington table talk that is politely received and promptly forgotten. Wallace thought nothing of it as he prepared for a speaking tour that would keep him on the road for several weeks.

“Ch. Sakarya’s Altin Kilij—First Anatolian Shepherd Dog AKC Champion,” by Deborah Drastrup, AKC collection, gift of Quinn and Marylin Harned

“We Can’t Afford to Anger the Turks!”

While Wallace was away, the State Department received a cable saying that two Turkish sheepdogs had been placed on board an Albanian ship bound for America. It seems the ambassador not only remembered his promise to Wallace, he had put it high on his to-do list.

After much travail, the immense dogs arrived in New York from Istanbul and were transported to Beltsville. There, it was discovered that the female was pregnant. Not only that, she was harboring a rare life-threatening parasite.

The first priority of the Sheep Dog Project’s director, a Dr. Morton, was to eradicate the parasite or else risk an international incident. “The Turks won’t like it if we have to destroy one of their dogs,” he said anxiously to a young research librarian who helped him identify the worm previously unknown in America. “With that war heating up again in Europe, everybody knows we’re bound to get involved, and we’ll need all the friends we can find around the world. We can’t afford to anger the Turks.” Wallace was kept informed by telegram, and Morton and the librarian endured many tense moments before the female was finally cured.

More anxiety attended the birthing. The female Anatolian delivered 12 healthy puppies. Actually, “healthy” is an understatement. The pups grew quickly, and before long the months-old pups were bigger than the adults of the other breeds housed at the secret facility. They were soon too big for their kennels, and more spacious pens had to be improvised with chicken wire.

Worse, all 14 of the Turkish behemoths had voracious appetites. By this time America was at war, and food rationing was the order of the day. Even the influence of Secretary Wallace couldn’t secure enough food to keep his pet project going. The research would have to be abandoned and the kennel liquidated. Beltsway was converted into a military K-9 facility. It was hoped that during the turmoil of a world war, the Turkish government wouldn’t notice that their national treasures had been sold as U.S. government surplus.

An auction was held to sell off the dogs, as discreetly as possible, to area sheepmen. The Pulik and Borders sold quickly, but the huge, exotic, and eternally hungry Turks were shunned by potential buyers. With both food and time running out, the fate of the Turkish sheepdogs hung in the balance.

At the last minute, a man from the Virgin Islands bought all of the Turkish dogs, loaded them into a big red truck, and drove away. Why he needed 14 enormous dogs, no one knew. Dr. Morton and his staff were so relieved to be off the hook for feeding the brood of giants, they didn’t bother to ask.

A noted authority on Turkish flock dogs is Marilyn Harned, of the Anatolian Shepherd Dog Club of America. In an AKC Gazette column, she described this obscure footnote to canine history and then asked, “Were these Turkish imports the first Anatolian Shepherds in the United States? For now, we believe they were.”

Postscript

This story went untold for decades. Then in 1993 the distinguished historian Dee Brown, author of “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee,” published his memoir “When the Century Was Young.” A chapter called “Dog Days” contained the full story of the Sheep Dog Project, told above in its merest outline.

Brown had a front-row seat for this offbeat drama. You see, he was the young research librarian who helped the anxious Dr. Morton identify the mystery parasite that nearly caused an international incident. His account concludes, “… And even now, all these years afterward, when I hear of or read about the Virgin Islands, I don’t visualize green hills or clean sandy beaches lapped by rolling waves under azure skies. Instead I think of 14 mammoth Turkish sheep dogs and all their hungry offspring overpopulating that tropical paradise.”

In this classic clip, a flabbergasted David Letterman encounters an Anatolian Shepherd Dog and a full-grown cheetah.

For more on the majestic dogs of the AKC Working Group, see “The Big Guys.”