Never mind Xbox Live or a day at the ballgame. A century and a half ago in the north of England, a working man’s idea of kicking back on the weekend was rag racing.

A contest of pure speed, the rag race was a straight-away course on which dogs galloped toward a finish line where their respective owners waited, frantically waving the pieces of cloth for which the event was named.

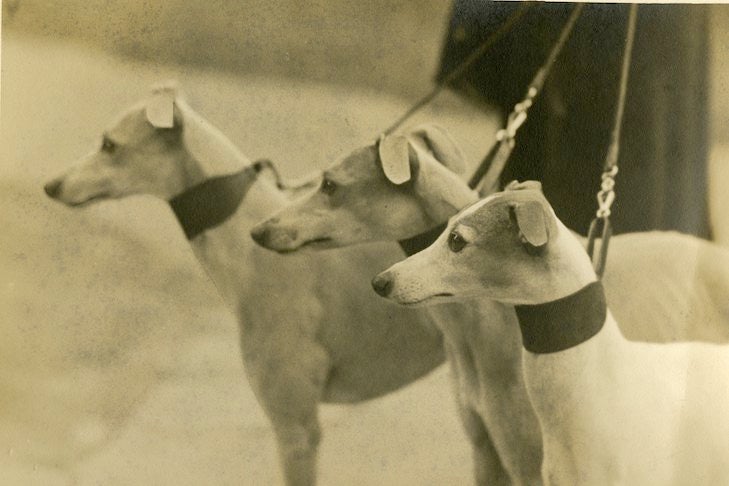

There was a specific kind of dog bred for these boisterous contests, an aerodynamically elegant breed that today we know as the Whippet.

The “Snap-Dog”

To be sure, for centuries, similarly smallish Sighthounds have been depicted in oil paintings and tapestries alongside royals and bluebloods, for all intents and purposes scaled-down versions of that ultimate speedster, the Greyhound. But it was among England’s hardscrabble miners and mill workers that the most complete template for what was dubbed the “poor man’s racehorse” emerged.

Nicknamed the “snap-dog” for the alacrity with which it grabbed prey, the Whippet reportedly derived its formal name from the English term “wappet,” which referred to a diminutive, yapping cur. From puppyhood, these homebred racers were taught to hone in on a scrap of towel or cloth, expertly launching themselves into the air to grab the fluttering fabric between their powerful jaws. As they grew more conditioned to this visual cue, the dogs would vocalize at even a glimpse of fabric, “wapping” so excitedly that the onomatopoeic name stuck.

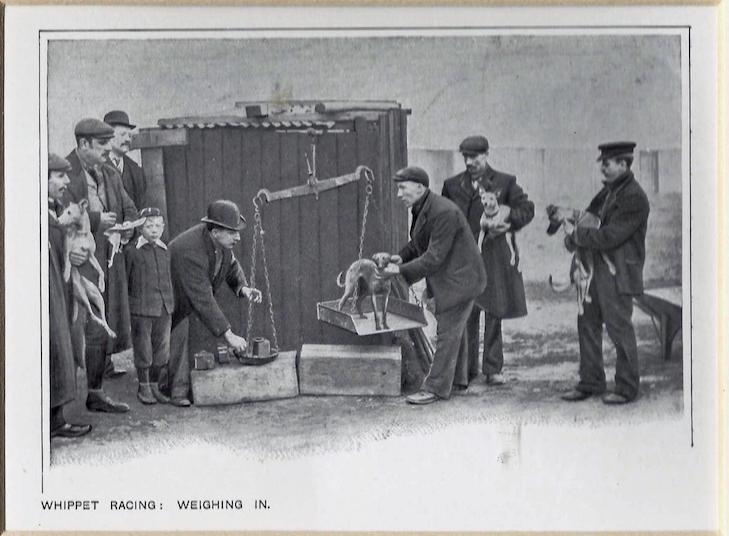

When it came to race day itself, the handlers waited at the start line for the boom of a pistol, the signal for releasing their dogs, though “release” is far too gentle a word: Holding the dog’s collar in one hand, lifting him by the base of the tail with the other, the handler would literally toss his dog forward, intent on giving him even the tiniest edge of position or stride to cross the finish line first. After all, bragging rights weren’t the only thing to be walked away with at these noisy gatherings, held on Saturday afternoons or Sunday mornings: Substantial cash prizes – sometimes as much as a week’s wages – were also at stake.

No Other Breed Could Keep Up

While some races permitted other breeds to enter, the Whippet soon became the ne plus ultra for racing these 200-yard straights – no comparably sized breed could keep up. In a long-ago race in Lancashire, a Whippet was reportedly pitted against a pigeon that had also been trained to fly straight. Released along with the Whippet, the pigeon won by two yards.

The exact recipe for breeding the Greyhound down to the Whippet’s handy racing size is lost to the mists of time. Italian Greyhounds, which are the toy version of the Greyhound, might have contributed the sinuous angles and compact curves that define the Whippet’s distinctive silhouette. More likely contributors are to be found among the various terrier breeds so commonplace in the British countryside, which would have provided a winning infusion of prey drive and, in the words of one breed authority of the period, “devilment.” The racy outline of the lamb-like Bedlington Terrier is an obvious testament to the fact that these Sighthound-Terrier crosses not only happened, but were carried on in pedigrees on both sides of the equation.

The focus of early Whippet breeders on function, pure and simple, explains the wide spectrum of color and pattern found in the breed, from brindles to particolors to solid blacks. During the Whippet’s racing heyday, black and whites were thought to be particularly flashy; in modern American show rings, particolor brindles tend to grab the judge’s eye; and among pet buyers, some breeders report that solid blue dogs are in constant demand. The one consistent thing that can be said on the subject of color is that according to the AKC standard – “Color immaterial” – there’s no such thing as a bad one.

From Racing to Show Ring

As English workers immigrated to the United States in the 19th Century, they brought their Whippets with them, and soon these sporting hounds populated Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and other New England states. Rag racing caught on in America as well, as far afield as the Midwest and California, even for a period taking place in racetracks designed just for that purpose, and targeted at gentleman sportsmen.

While the commercial appeal of the races eventually faded, the siren call of the breed certainly did not. In the waning years of the 1800s, Whippets entered the show ring, and have progressively made their mark as eye-catching show dogs whose bodies and minds are still capable of doing the job for which they were bred.

Rather than racing amid a whooping gallery, or darting into the underbrush to help a farmer poach a rabbit for the pot, these days most Whippets have found favor as consummate companions: generally agreeable and easy keepers, with a tolerance for children and even cats and other animals if care is taken not to ignite their still-percolating prey drive.

Even back in their early racing days, Whippets have always appreciated creature comforts, something that an early expert cautioned about.

“Never let your working Whippet get soft,” warned Freeman Lloyd in his 1904 classic “The Whippet or Race-Dog.” “If he is inclined to take naps under the fire-place, help him out of it with a gentle reminder. If you allow him to have his way in these matters, he will soon cut his work, and make for home when he is wanted.”

Today’s Whippet

While many Whippets have made a world-class sport out of sofa snoozing, the spirit of the snap-dog still lurks under that tautly muscled exterior. Whippets are numerous – to say nothing of successful – competitors at AKC lure-coursing trials, a kind of simulated, looped-course rabbit hunt that uses a white plastic garbage back in lieu of a “bunny.”

And a version of rag racing is still alive and well today – minus, of course, the wagering, the dog tosses, and those eponymous rags. Straight racing, conducted under the auspices of two national organizations –the Continental Whippet Alliance and the Whippet Racing Association – employs the same 200-yard straight-away course (sometimes 150 yards, in particular for puppies), with owners awaiting their fleet-footed Whippets at the finish line.

The dogs are released simultaneously from a metal or wood start box, so each has a fair start, or are hand-slipped (again, minus the tossing, thank you). The waved towels have been replaced by a faux-fur lure that makes an irresistible squeaking noise as it bumps along the ground.

And the Whippets themselves? They are unchanged from their predecessors of centuries past – eyes keen, muscles coiled, voices raised, waiting for the second they will be unleashed in a burst of speed and intensity. And then, hours later, you will find them back on the couch – dreaming, doubtless, of the fuzzy squawker that got away.