Though we often don’t think about them in this way, dogs are really about people — those long-ago (or, sometimes, not so long-ago) figures who developed particular breeds for particular tasks. Some breeds — like the Doberman Pinscher, Teddy Roosevelt Terrier, and Cesky Terrier — owe their existence to just one visionary person. Other breeds were brought into being by specific cultures or classes of people.

If civilization is the intersection of a group of people with their environment, so too are their dogs: With coats that evolved to survive the local climate, body styles developed to navigate native terrains, and characters that fit into the social mores of the day, our purebred dogs are living, breathing moments of history, reflections of the far-flung cultures that developed and nurtured them. Through them, we rediscover our globe’s cultural diversity and heritage.

Each week, without even leaving our couches, we travel to a different place and time to meet the people who developed the snoozing bundles of fur at our sides.

***

A pilgrimage isn’t just a physical trip. It’s also an internal journey whose final destination is, hopefully, understanding.

For Leonberger lovers, one of the ultimate rites of owning their giant, gentle breed is to visit the eponymous German town where it was created. There, in the center of Leonberg’shistoric marketplace, ringed by traditional half-timbered houses, they take the obligatory photo in front of its fountain.

Leonberg’s fountain, unfortunately, doesn’t depict any Leonbergers. When it was built in the mid-1500s, the breed didn’t exist – and wouldn’t for another three centuries. But the fountain does sport Leonberg’s coat of arms, depicting a lion rearing on its hind legs. And breed lore says that noble beast inspired this shaggy-coated, regal dog, which soon became a must-have among those who were so well-heeled their families often had crests of their own.

If you do want to find a statue of a Leonberger to pose next to in Leonberg, there is a bronze one erected in 2005 in an out-of-the-way commercial area. And in a way, the dichotomy between these two photo ops encapsulates the interesting beginnings of what some have called the “secret mascot” of Leonberg: Somewhere between the lofty fantasy of a leonine dog and a craftily marketed luxury item arising out of less-than-plush conditions, there is the breed that today we know as the Leonberger.

A Very Intentional Creation

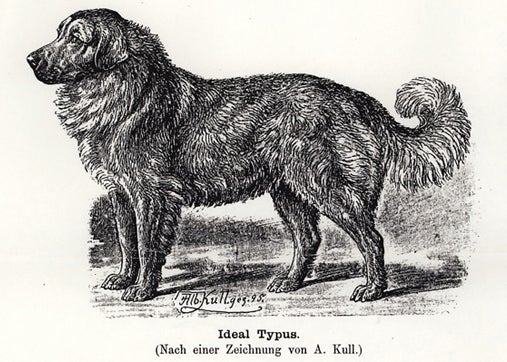

Unlike many breeds that were forged by happy accident – a job needed to be done, and a random dog excelled in it because he was a certain size or shape or color – the Leonberger was a very intentional creation. The man who brought the breed into being was Heinrich Essig, a city councilor and dog dealer in Leonberg.

A dog dealer is just what it sounds like – someone who breeds and sells dogs for profit. Since the 1680s, Leonberg’s market square was also the site of a famous horse market, or Pferdemarkt, that continues to this day. So the citizens of mid-19th-Century Leonberg were accustomed to the buying and selling of livestock – and dogs were considered just that.

Owners across the globe included royals like King Umberto I of Italy, Tsar Alexander II of Russia, and England’s prince of Wales.

For his part, Essig – whose last name means “vinegar” in German – was an astute marketer and salesman, at one point selling more than 300 dogs a year. Breeding his first Leonberger litter in 1846, which is generally accepted as the year the breed was founded, Essig was said to have crossed a Landseer Newfoundland and a short-haired Saint Bernard acquired from the famous Swiss hospice that gave the breed its name. Later, he reportedly added a dose of Great Pyrenees, though there are no records to confirm any of this. Large, coated dogs owned by farmers and butchers were common in southern Germany in this period, and went by many names. But it was Essig who had the vision – not to mention the marketing skills – to formalize them into a bona-fide breed.

A Teddy Bear Dressed as a Lion

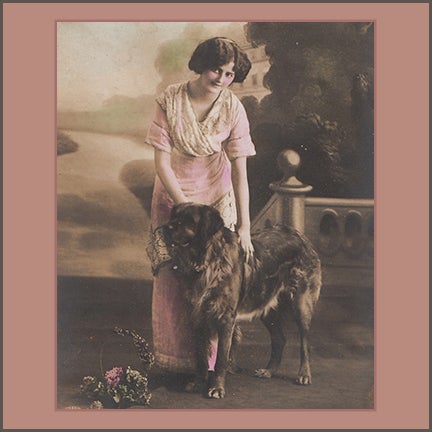

Gifting dogs to high-profile figures to help establish their cachet, and lending them to popular illustrators to use as models, Essig sold Leonbergers to a veritable Who’s Who of prominent 19th Century figures. Owners across the globe included royals like King Umberto I of Italy; Tsar Alexander II of Russia; England’s prince of Wales, who later became King Edward VII, and Empress Elisabeth of Austria, better known as “Sissi,” who owned seven of  Essig’s dogs. Leonbergers also graced the estates of national leaders like Napoleon II and III, and Otto von Bismarck; the composers Richard Wagner and Sergei Rachmaninoff, and Italian patriot Giuseppe Garibaldi.

Essig’s dogs. Leonbergers also graced the estates of national leaders like Napoleon II and III, and Otto von Bismarck; the composers Richard Wagner and Sergei Rachmaninoff, and Italian patriot Giuseppe Garibaldi.

As with any successful business enterprise, there were copycats. But Essig painstakingly nurtured his “brand,” sending the elegant yet substantially boned dogs as far afield as Japan, Russia and the United States. In the early years of the breed, Essig tried to produce white dogs because they were popular. It wasn’t until after his death in 1899 that the tawny, lion-colored coat – complete with mane – and signature black mask became fixed and indelibly associated with the Leonberger.

Variation in color and appearance aside, Essig bred for one trait that is universal in the breed, even to this day – an affectionate, stable temperament that proves irresistible to everyone they meet. Dogs of this imposing size needed to be even-tempered, never timid nor aggressive with people or other dogs. Gentle and playful in direct proportion to their formidable size, temperamentally Leonbergers are more akin to a cuddly teddy bear than the aloof lion that was supposedly their inspiration.

Leonbergers were dismissed in some quarters as Saint Bernard wanna-bes, and at dog shows they were often lumped in with other breeds, or not permitted to be shown at all.

Saint Bernard Wanna-bes?

While the newly imagined Leonberger was a resounding success with owners, its reception by Victorian dog authorities was mixed at best. Essig’s refusal to write a standard or memorialize parentage in pedigrees – after all, he reasoned, he knew what his dogs should look like and how they were related – led to ongoing friction with the nascent dog-show fancy. Leonbergers were dismissed in some quarters as Saint Bernard wanna-bes, and at dog shows they were often lumped in with other breeds, or not permitted to be shown at all.

While the newly imagined Leonberger was a resounding success with owners, its reception by Victorian dog authorities was mixed at best. Essig’s refusal to write a standard or memorialize parentage in pedigrees – after all, he reasoned, he knew what his dogs should look like and how they were related – led to ongoing friction with the nascent dog-show fancy. Leonbergers were dismissed in some quarters as Saint Bernard wanna-bes, and at dog shows they were often lumped in with other breeds, or not permitted to be shown at all.

Given this hostility from the burgeoning dog-show world, it’s a wonder that the Leonberger survived beyond Essig’s lifetime. But survive it did, even through the challenges and deprivations of two world wars. The Leonberger also gave back to two breeds that were instrumental in its development: In the 1870s, Essig shipped three Leonberger puppies to Newfoundland breeders in Canada to help add such much-needed fresh blood to the breed. And years before, when Essig acquired a Saint Bernard from the Great Saint Bernard Hospice for his Leonberger breeding program, Essig paid the monks in trade with two of his dogs. Until that point, the hospice’s Saint Bernards were short-coated, and documentation suggests that the long-haired variety may very well be the result of this and later Leonberger contributions.

Today’s Leonberger

Early Leonberger imports were exhibited at New York City’s famous Westminster show throughout the 1880s,and the breed has been continuously present in the United States since the 1970s. But the Leonberger was recognized by the American Kennel Club just a mere decade ago.

While the Leonberger may have only recently entered the consciousness of American dog lovers, the breed has been waiting, with its characteristic patience and docility, for centuries. Even if Leonberger owners never get to stand before that lion-crested fountain in a small town on the outskirts of Stuttgart and smile for the camera, no matter. The big dog with the equally big heart lying at their feet is the ultimate memento.