It was the canine version of the Titanic – but with far less tragic results.

In 1807, a ship left Newfoundland, Canada, bound for the English harbor of Poole in Dorset. Off the Maryland coast, it encountered a heavy gale, and began to take on water. With the smaller boats on the brig swept out to sea, the chance of rescue was bleak. Acknowledging their grim fate, the sailors began to drink, ushering in a more pleasant oblivion than the one that was surely coming.

But salvation did arrive, in the form of a boat named the Canton. Its crew members boarded the foundering British ship and rescued all the survivors – not all of them human.

Though cod made up most of the cargo, the ill-fated ship did have two dogs aboard. And like the salted oceanfish in the hold, this breeding pair was also considered a valuable export.

Both the shipwrecked canines – the male, “Sailor,” and a female later named “Canton” in honor of the vessel that saved her – were St. John’s Water Dogs. Also called Lesser Newfoundland Dogs, they were a breed of hardy and water-obsessed dogs valued by Newfoundland fishermen for their ability to haul lines and nets of fish back to their boats. As you might guess, there were also Greater Newfoundland Dogs, which were, logically, larger in size but just as water obsessed. Both the Lesser and Greater Newfoundland dogs eventually evolved into what we today know as the Labrador Retriever and the Newfoundland, respectively.

Had they reached their final destination across the pond, Sailor and Canton would have likely been sent to one of the several British estates that was developing their kind to be a tractable, biddable gentleman’s retriever. But their abrupt detour on our shores redirected them to a completely different destiny as the canine Adam and Eve of a new and totally American breed – the Chesapeake Bay Retriever.

The Sailor Breed

Sufficiently sobered, the English crew were deposited at the nearest port in Norfolk, Virginia. But the two dogs stayed aboard the Canton, having been purchased for a guinea each by George Law, a nephew of the rescuing ship’s owner. His final destination was Baltimore.

That 200-mile journey from up the coast from Virginia to Maryland gave Law time to assess his spur-of-the-moment purchase.

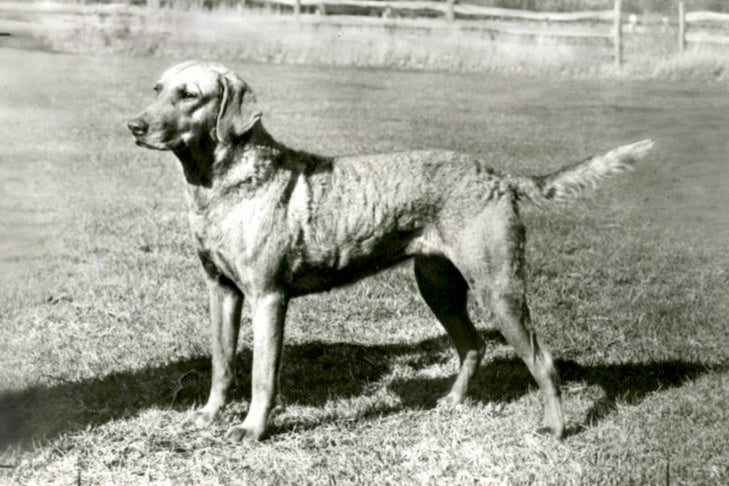

Neither dog was overly large. Sailor, the male, was described by Law as “dingy red” in color, with a short but very thick coat, while Canton was black.

“Both attained great reputation as water-dogs,” Law wrote in an account almost 40 years later. “They were most sagacious in every thing, particularly so in all duties connected with duck-shooting.”

Law described Sailor in particularly glowing terms, calling him “figure-lofty in his carriage, and built for strength and activity; remarkably muscular and broad across the hips and breast …” Of note were Sailor’s “peculiar” eyes, which were “so light as to have almost an unnatural appearance,” he wrote.

Law had learned from the English ship’s captain that Sailor and Canton had been specifically chosen from unrelated families, presumably so they could be bred together.

Sailor went to John Mercer of West River, who after a period sold him to Governor Edward Lloyd in exchange for a Merino ram; during the early 19th Century, a craze for those Spanish sheep resulted in them being sold for “many hundreds of dollars,” according to Law – approaching five figures in today’s money. Lloyd took Sailor to his shore-side estate, where, Law reported, “his progeny were well known for many years after; and may still be known there, and on the western shore, as the Sailor breed.” Indeed, Law added, when he visited the area 20 years later, he noted a number of dogs who had the same peculiarly light eyes as Sailor.

For her part, Canton went to Doctor James Stewart of Sparrow’s Point, where she remained until her death. Like Sailor, she too was well known for the quality of her progeny, which, Law said, had a reputation in the field that was “unsurpassed” among duck hunters.

The All-Around Water Dog

Sold to separate individuals in different parts of the Chesapeake Bay area, Sailor and Canton presumably were never bred together, though some of their descendants inevitably were. While the two provided the foundation for the Chessie, other breeds naturally were crossed with them to create the waterfowl hunter we know today. Local coonhounds were very likely one contributor, added to improve scenting ability.

While the dogs’ Canadian maritime roots gave them an inherent ability to work in frigid water, their new environs in an estuary, where fresh and salt water mix, required some modifications. The Chesapeake Bay Retriever’s dense, wooly undercoat contains an abundance of natural oil, making it ideally suited for the frigid bay, where the dogs sometimes broke through ice to complete their retrieves. The breed’s distinctive hindquarters, which can be a trifle higher at the hip than at the withers, contributed to its strong rear drive, especially helpful in the marshy footing of the wetlands.

Chesapeake Bay Retrievers were not just popular with hobby hunters, who used them to retrieve the mallards, red-heads, and canvasbacks that they shot along the rivers feeding the estuary. On a larger scale, market gunners used the dogs to retrieve hundreds of birds a day; they would then guard the catch and gear from thieves who would otherwise gleefully skip off with the day’s hard-earned work. As a result, the Chesapeake developed a tendency for protectiveness and independence that makes the breed a less-than-ideal fit for most first-time dog owners.

In the Ring and Field

As the 19th Century drew to a close, the descendants of Sailor and Canton had become quite numerous, as did the names ascribed to them, which included the Brown Winchester, the Otter Dog, the Newfoundland Duck Dog and the Red Chester Ducking Dog. In 1887, a group of “Chesapeake Ducking Dog” enthusiasts convened at the Poultry and Fancier Association Show in Baltimore to agree that the Sailor and Canton strains should be considered one breed, albeit divided into three “classes” to accommodate their differences of color and coat: otter dogs, which were a “tawny sedge” in color and had short, wavy hair; and the curly-hair and straight-hair versions, which were red-brown. By this time, Canton’s black coat was no longer part of the breed; even today, that color along with the rear dewclaws that were found on both dogs are disqualifications in the Chesapeake Bay Retriever standard.

A year later, in 1888, the breed was recognized by the American Kennel Club – the first retriever to receive this formal acknowledgment. In 1918, a more unified vision of the breed – with a short, hard, double coat that tended to wave on the shoulder, neck, back and loins, and those yellow and amber eyes passed down by Sailor – was accepted by the AKC as the Chesapeake Water Dog.

Today, more than a century later, the breed’s name still retains mention of the watershed with which it is so indelibly linked. (In truth, the whole of Maryland lays claim to the Chesapeake Bay Retriever, having named it the official state dog in 1964.) And once Sailor and Canton’s many generations of offspring adapted to their new home, they stayed true to their purpose: Unlike so many other Sporting breeds, Chesapeake Bay Retrievers do not have a schism between conformation and performance: The contenders you see in the ring are those you’ll find in the field. And these bird-obsessed dogs assuredly wouldn’t want it any other way.