I have discussed anthropomorphism in the past and posted some links on Facebook yesterday on the subject. I always feel guilty for throwing out a “five dollar” word, but its understanding is vital to the success of this program.

“Anthropomorphism is the use of human characteristics to describe or explain nonhuman animals.” This subject is hotly debated among scientists. They do agree, however that as a logical bias, it can lead to faulty assumptions about the internal motivations of your dog. It is better to worry more about what you are “saying” to the dog, than to believe you know what the dog is saying in their own mind. When working with a dog, everything becomes a signal to perform or not perform a behavior. The environment, your body language, your tone of voice, and how you set up the behavior will all be received by the dog. Often there are conflicts in the signal forcing the dog to decide where their valence (stress response or pleasure response) directs them. The wind is blowing fiercely, you are not in the same position, your tone has lowered, and your body language is not engaging. All these contextual factors influence the dog. When the dog doesn’t perform correctly, the anthropomorphized response is “You see! He doesn’t want to perform the behavior.” Is that the dog’s true internal state or has the dog read the mixed signals, found them stressful, and refused?

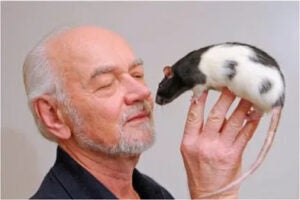

Jaak Panksepp sits in the middle of the debate on anthropomorphism. Mainly because he addresses behavior through primal emotion versus traditional cognitive process. However, he did lecture on the simplicity of animal behavior. Paraphrasing from a 2014 animal training conference, “The animal simply seeks pleasure and avoids stress.” If you start with this proven concept, you can avoid a great deal of anthropomorphism. It makes us conscious of our mixed signals (for example, you always point to the ground for a down and then you don’t). It helps us avoid self-fulfilling prophecies (“I knew he did not want to do that”). It minimizes elaborate excuses and justifications on the handler’s behalf (“He has never done that before”). It allows us to critically look at our training and determine how the dog’s valence (a scale of stress to pleasure) and arousal impacts the dog’s ability to perform a desired exercise. Further, it makes the trainer responsible for controlling all the variables that contribute to success.

The basis for detection dog behavior is very simple. A dog that is in continual and complete anticipation of finding an odor that they associate with a reward. The complexity is the added layers of distraction and the physical challenges to get closer access to the odor. A good dog relies far more on their own abilities, then spends time referring to the handler. This is the very reason why we have dogs doing detection work, they are better at this task than are humans. Assigning layers of human reasoning and emotions diminishes the value and the ability of the dog.

We know the end goal, a dog that will be deployable as an explosives odor detection dog with federal agencies. A majority of dogs will not meet that goal. Your dog will be handed to an assessor who will simply want to watch the dog perform the exercise. The person assessing the dog will not be referring to a long check list of anthropomorphic reasons, excuses, and justifications. A dog looking to the handler to help them through each level of assessment will be rejected. The dog will be selected solely on the basis of its independent ability to perform the tasks.