With their ever-wagging tails, handsome appearance, soulful eyes, and friendly temperament, the merry Cocker Spaniel has deservedly often been in the ranks of most popular dog breed. In fact, the breed was number one in AKC rankings from the late 1930s to the 1950s, and then again during the mid-1980s.

Along the way, a divergence in type had emerged between strains of slightly smaller, shorter-muzzled Cockers being developed in the U.S. and the original, longer-headed dogs that had come over from England. The two were ultimately split into different breeds in 1947, with the American version continuing to be known simply as “Cocker Spaniel” in the U.S., and the other type classified as English Cocker Spaniels. (What we know as “Cocker Spaniel” in the U.S. is known as “American Cocker Spaniel” in the rest of the world—likewise, what we call the “English Cocker Spaniel” stateside is known as simply “Cocker Spaniel” everywhere else.)

The Cocker Spaniel’s great popularity in the U.S. in the first half of the 20th century led to frequent use of images of the breed in advertising, prints, and greeting cards. A female Cocker even hit the silver screen in a big way as the demure, long-eared love interest in the 1955 Disney film Lady and the Tramp.

Appealing depictions of Cocker Spaniels were very popular in print advertisements and greeting cards in the early to mid-20th century.

Today’s Cocker is descended from dogs originally bred to help provide food for the table years ago in Europe and the British Isles, where a medium-sized, energetic, and eager-to-please dog with strong hunting skills was needed.

Land Spaniels to Cockers

Writing in 1667, Nicholas Cox describes small land spaniels of courageous mettle, “strong, lusty and nimble rangers, of active feet, wanton tails and busy nostrils”—still a good description of the Cocker Spaniel.

A less flattering description was given in 1647 by the “Witch-Finder General,” whose dubious job it was to rid England of witches, when he stated that one of the witches’ familiars (evil spirit friends) was a fat spaniel, without any legs, named Jermara.

As with the other breeds, the advent of the gun affected the Cocker. Sportsmen needed much time to load and aim, and the merry, active (and impatient) Cocker was a nuisance; a slower, quieter dog was wanted, and the Cocker fell out of favor. It was soon seen mostly around London as a pet rather than a hunting companion. As with most things, this changed, and by the mid-19th century, Cockers were back in favor as working bird dogs. A minimum weight of 14 pounds was established to eliminate the then-popular toy spaniels from competing.

With the advent of shows, the problem of separating the spaniels resurfaced. If a dog was small he would be shown as a Cocker and when he grew bigger he would be shown as a Springer. In the 1870s, all Cockers were classified as Field Spaniels—even Mr. Farrow’s famous dog, Obo, was first shown as a Field Spaniel. By the end of the decade, the rage for black Field Spaniels had taken hold, and classes were now being offered for them. In 1883, a class for Cockers was offered, and Farrow showed Obo as a Cocker. Still, the confusion was not over, as the Cocker classes were open to “Spaniels, Cockers, and other small Fields.” It was 1892 before a class was offered for Cockers only.

From the start of the new century until after World War I, the advance of Cockers in England was consistent, without being sensational. But on the resumption of shows in 1920, registration skyrocketed. Finally, in 1935, Cockers became the most popular breed in England, eclipsing Wire Fox Terriers in annual registrations with the Kennel Club.

The Cocker Spaniel in Art and Literature

With the breed’s long history and perennial appeal, it’s not surprising that Cockers have made many appearances in art and literature.

Spaniels of medium size have been depicted in art for centuries, going back to the representations of hunting dogs with silky coats and low-hanging, fringed ears found in the richly illustrated Livre de Chasse (Book of the Hunt) by Gaston de Foix in 1388, which specifically mentions spaniels being used in the sport of falconry.

The tradition of depicting dogs in hunting scenes continued through the 19th and 20th centuries, and a number of respected artists became known as specialists in animal portraiture. Among them was Maud Earl, who painted a beautiful portrait of the buff Cocker Ch. Lucknow Creme de la Creme in the field. Creme de la Creme was sired by the famous dog Red Brucie, who also sired Ch. My Own Brucie, who went Best in Show at Westminster in 1940 and 1941.

Ch. Lucknow Creme de la Creme, 1931, by Maud Earl (AKC Collection)

Cocker Spaniels have had starring roles over the years in many dog books, including novels, poetry, and memoirs. Among the most memorable, perhaps, is a much-loved, poignant story featuring the breed that was written years ago for young readers.

“You have to give Princey a chance …”

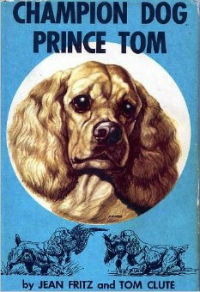

Many adults still fondly remember today as their favorite childhood book a modest little paperback called Champion Dog: Prince Tom, by Jean Fritz and Tom Clute (Scholastic Book Services, 1958; out of print but available through resellers), that was available to schoolchildren in the 1950s and ’60s through Scholastic’s Weekly Reader program.

Champion Dog: Prince Tom tells the true story of a buff Cocker Spaniel who was

the runt of his litter but through his spunk and talent and the dedication of his owner becomes a trick dog, television star, obedience-trial whiz, and finally the first American Cocker Spaniel to win the Cocker National Field Championship, in 1956.

Dog lovers share reminiscences of reading the book over and over again as a child, and for many the book instilled a lifelong affection for dogs in general and Cocker Spaniels in particular. For some people who ended up in the dog sport as a lifelong pursuit, it was the book that first kindled an interest in the many forms of enjoyable competitions and activities for dogs.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Devoted Cocker Spaniel

Another memorable appearance of a Cocker Spaniel in literature is of a very different genre. The well-regarded English poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning, who was an invalid for most of her life, dedicated an entire poem to describing the devotion and vivacious beauty of her beloved Cocker Spaniel, Flush, who rarely left her bedside. Here are some excerpts:

Leap! thy broad tail waves a light;

Leap! thy slender feet are bright,

Canopied in fringes.

Leap—those tasselled ears of thine

Flicker strangely, fair and fine,

Down their golden inches. […]

Of thee it shall be said

This dog watched beside a bed

Day and night unweary—

Where no sunbeam break the gloom

Round the sick and dreary. […]

Therefore to this dog will I

Tenderly not scornfully

Render praise and favor!

With my hand upon his head

Is my benediction said

Therefore, and forever. […]

Blessings on thee, dog of mine,

Pretty collars make thee fine,

Sugared milk make fat thee!

Pleasures wag on in thy tail—

Hands of gentle motion fail

Nevermore to pat thee!

—from “To Flush, My Dog,”

by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Popularity of Cockers in the U.S.

Cockers had come to the United States during the latter half of the 19th century, but 1884 marked the arrival of Obo II, a 23-pound son of Farrow’s Obo. Obo II was ancestor to Robinhurst Foreglow, the dog that changed the Cocker, creating the more modern dog—up on leg and shorter of back. All of today’s winning Cockers trace back to one or another of Foreglow’s four sons. Just as in England, the popularity of the Cocker exploded during the ’20s and ’30s. A division in type was emerging between what started to be called the English and the new American types. By 1936, there were three separate varieties shown—Black, Parti, and English. Later, a fourth division was added for the ASCOBs.

In 1935, the English Cocker Spaniel Club of America was formed to promote interest in the English Cocker, as separate from his American cousin. Geraldine R. Dodge, president of the club, instituted an extensive pedigree search back into the 19th century. In 1940, the Canadian Kennel Club recognized the English Cocker Spaniel as a separate breed, and the American Kennel Club followed in 1946.

A Cocker Spaniel: The Embodiment of Joy

To love this breed is to be caught up in its ever-happy temperament. The breed standard says, “Above all, he must be free and merry.”

American scholar and writer Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, author of Dogs Never Lie About Love: Reflections on the Emotional World of Dogs, captures in a brief word-picture the unbridled joy that is a Cocker Spaniel:

Every time I told my Cocker Spaniel, Taffy, my very first dog, that we were going for a walk, she would launch into a celebratory dance that ended with her racing around the room, always clockwise, and faster and faster, as if her joy could not be possibly contained. Even as a young boy I knew that hardly any creature could express joy so vividly as a dog.

There is indeed much to love about the joyous, devoted Cocker Spaniel, as confirmed and celebrated by the breed’s fans over the years. May his tail ever wag.